by Jim Thompson

What seems to be a rather routine procedure may not be. At various times a beekeeper finds that the queen needs to be replaced. Different reasons for this replacement might be: the queen is old or failing, the attitude of the hive is not what you would like it to be, the hive is non-productive, the hive needs a break in the brood cycle to clear up disease, you may want to retard the hive from swarming, or there is no queen in the hive.

When introducing a queen to a hive, there are the different techniques or procedures that can be used: introduce a mated queen, introduce a virgin queen, introduce a queen cell, or encourage the bees to raise their own queen. The percentage of acceptance by the bees in the installation of a laying queen is rather high. The acceptance of a virgin queen by the bees in a hive is the range of 50 to 60%. While putting in queen cells or allowing the bees to raise their own queen may also have a high percentage rate of acceptance, there are further conditions that the hive must have in place. When raising a queen from a cell more time is required for the queen to develop, get mated, and start laying eggs. The amount of time could be critical if the nectar flow is missed or the drones have been eliminated from the other hives, or the weather is not conducive to bee flight.

There are many devices that beekeepers have invented for queen introduction and some of the situations within a hive make queen introduction difficult. It also seems that every beekeeper has their own way of doing things and their way seems to be the only way to do things. So when you talk to other beekeepers, the more confused you will become. When you add all of these factors, the “simple task of introducing a queen” is not so simple.

If you decide that you are going to requeen a hive by installing a laying queen, the normal procedure is to order a queen. A day before you install her, you either catch the old queen and put her somewhere other than in that apiary or kill her. You need to be assured that the hive is queenless. There is some debate on whether you leave the body of the old queen in the hive or remove it if your choice was to kill her. One thought is to have the bees carry out the body of the old queen so they are absolutely sure that they are queenless. Another thought is that even a dead queen could emit a residual amount of the queen substance pheromone indicating that they are queen right. Perhaps in your efforts to kill the queen, you only stun her or injure her and thus the situation is worse by having a wounded queen in the hive emitting pheromones when you believed that she was dead. If your choice was to remove the old queen and move her to another yard, you will have the advantage of having a queen in case something goes wrong. However she may still have the problem that caused you to want her replaced.

If you wait too long before introducing the new queen and the hive is queenless for a while, there is the possibility that a worker(s) will assume the duties of laying eggs. This is known as a laying worker(s) and all these eggs will develop into drones.

Laying workers are very difficult to find as they look like all of the other workers and the hive has accepted them as queenlike. A tell tale sign of laying workers, is that the eggs in the cells are not well centered and in many cells there are multiple eggs. Some say that solving a laying worker situation can be solved by multiple attempts in introducing queens, while others say that the hive is hopeless and the hive should be combined with a strong queen right hive. The reason that the combining method works is that the pheromone of the laying queen is stronger and usually the hive has a larger population.

A California queen cage.

A queen that is failing sometimes will lay only eggs that will develop into drones, thus she is called a drone layer. Because of her appearance, she can be identified easily and caught so the situation can be corrected by requeening.

By requeening every year you generally prevent having a failing queen for whatever reason. A new or young queen tends not to swarm as much as an older queen and usually the disposition of the hive is calmer.

Many beekeepers believe that the bees are a better judge on the condition of the queen, and if she needs to be replaced they will develop supersedure cells. You can tell the difference between supersedure cells and swarm cells usually by the position that the cell occupies on the frame. A supersedure cell can be anywhere on the frame as it was built out of necessity, but usually it is in the middle part of the frame. A swarm cell usually is on the bottom part of a frame and usually there are several cells. You should also be aware that many times bees will build queen cell cups on the frames and it is worth inspecting to see if the cup is polished and being primed with royal jelly or already have eggs present.

A general rule is that you do not destroy supersedure cells. If you start destroying swarm cells in hopes of preventing swarming, you may end up with a hive that swarms and leaves your hive queenless. If you see the swarm cells, the bees have made the decision to swarm and there is little that you can do to prevent it. You can split the hive, and use the cells to queen the split(s), while keeping, or replacing the queen in the original hive.

Swarm cell hanging from the bottom bar of a frame.

It is also handy to know how to read what is happening to the queen cells in a hive. When you see open queen cells, you should look at the bottom of the cell to see if the queen emerged from the cell or was killed. An emerging queen chews the bottom of the cell open so the bottom of the cell will swing open like a trap door. A queen that has been killed in her cell will have evidence where the cell was opened from the side of the cell.

More controversy exists as to how long a queen may live and store semen. Most of the books indicate that queens living under normal conditions will last approximately two years. As proof, the books point out that when a hive swarms, the swarm begins to make supersedure cells in the newly established hive. However if a beekeeper can keep the hive from swarming, there will be days where the queen cannot be found in the hive and there are no eggs but a few days later everything is back to normal and a queen is present. This indicates that the original queen took another mating flight or was superseded.

Supersedure cells in the middle of a frame.

You also should know the usual timing procedure of a swarm. The bees around the queen decide when the hive should swarm and build many queen cells and start reducing the diet of the queen. The queen stops laying eggs and shrinks in size so she can fly. When the swarm issues, we call it the primary swarm and because it may have the old queen and the bees usually settle at a low location. Scout bees are already looking for a new home and when decided which of possibly several locations is best they go directly there.

If the weather is good, a queen will emerge from a cell in the original hive and take her maiden flight about three days after the primary swarm issued. Sometimes the timing gets off and another swarm issues from the hive and this is called a secondary swarm. Because the old queen has gone in the previous swarm, the queen or queens in this swarm are virgin queens.

I have seen a secondary swarm with seven queens and was busy catching them and putting them in mailing cages. A secondary swarm usually settles on higher objects and once hived takes longer to start up as there is the decision which queen will be dominant and the mating flight or flights will be done after the hive is established. If too many secondary swarms issue from the same hive, there is the possibility that the hive can go queenless as there aren’t eggs or larvae that are of the right age to make a queen.

A very successful method in getting ready for the introduction of a new queen is to build a Nuc (nucleus hive) by removing the frame that the queen is on along with a frame of honey and a frame of brood with the hanging bees and take them to a new location. I mentioned three frames but you could have more, it just depends upon the size of the Nuc, most beekeepers prefer five frames. You may take frames from other hives and put into the Nuc as long as you do not include the hanging bees.

Essentially what you have done is remove the old queen from the original hive in preparation for the introduction of a new queen and provide the old queen an opportunity to build up a small hive while also giving you a backup queen in case something goes wrong with the original hive.

Sometimes this is considered a method of swarm control. In the old hive you have the essentials for queen rearing such as larva of the correct age, plenty of bees to provide the bees with heat and hive duties, and plenty of food. In case the introduction of the new queen does not work, they could raise their own queen. If in the case you didn’t purchase a queen, you could use this technique as the hive may develop supersedure cells. You must take the nuc to a new location as they will return to their original hives if left in the same yard. As the nuc grows, it may be transferred to a regular hive.

A five-frame nuc.

If you purchase a queen, normally that queen has been mated and has been laying eggs. She is sent to you in a mailing cage which over time has had many configurations. The mailing cage can be made of wood with two or three “holes”, metal, or plastic. There will be room for the queen and a few attendants, ventilation, and a compartment that holds queen candy. There usually are two outlets in the cage so that the queen may be released directly or released after the candy has been eaten.

Queen candy is usually made of a mixture of finely ground confectioner’s sugar and high fructose corn syrup. If you were making a queen candy for your use, several beekeepers have used a mixture of honey and powdered sugar. Some people have claimed that using honey in the mixture may contain pathogens. Getting the candy to the correct consistency is very important as if it is to thin, it will not stay in the correct location of the cage and if it is too hard, the bees will have trouble eating it. The hardness of the candy has led to the idea that you should poke a hole through the candy with a nail.

Some beekeepers have used marshmallows instead of the conventional candy to get away from the consistency problem. The idea of using the candy is to provide the queen with food during her transportation to her new home and to provide a slow or timed release of the queen. The timed release is very important as the bees in the hive need time to accept the queen. However, there are still a bunch of questions. Where and how do you place the cage? Do you remove and replace the workers? Do you direct release the queen? Do you treat the hive for mites and other diseases while introducing the queen? Many of the answers to these questions depend upon your own experiences, training, and schedule.

If you are putting a queen in an apiary that is miles away from your home, you may wish to remove the “cork” from the candy end because it may be some time until you return to the yard. If the hive that is receiving the new queen is in your front yard, you may wish to keep the cage corked until you choose to release the queen at a later date.

Many years ago, it took nearly a week for a package of bees to be delivered in the mail, allowing the bees’ time to become accustomed to the queen. Thus beekeepers got in the habit of releasing the queen directly into the beehive. Today, some beekeepers are receiving packages that were shaken within the last 24 hours, so there needs to be some time where the queen is kept caged.

When you place the mailing or introduction cage in the hive, care must be given to not put the cage directly underneath where a top feeder is located. This is just a precaution in case the feeder malfunctions and drowns the queen in her cage.

There is a lot of discussion about how to place the cage in between the frames. Generally the candy end of the cage is higher than where the queen is located. The reasoning for this is that if an attendant bee dies and covers the candy, she traps the bees in the cage. Thus some suggest removing the attendant bees, while others suggest that the attendant bees should be replaced by bees from the colony where the queen is being introduced. Some queens are sent in bulk packaging meaning that several queens are in their own mailing cages without attendants. The balance of the bulk package is filled with loose bees to feed the various queens in the package.

I would suggest that no chemicals be used to treat diseases and mites during the period of time that a queen is being introduced as it could interfere with the pheromones of the queen. Once the queen is released and laying eggs, the chemicals for mite control could be started.

Some beekeepers advocate that the laying queen should be confined to a certain frame or within a special area. It seems that once a queen is laying eggs in a hive, her acceptance is very close to 100%. Other reasons for confining a queen is to be able to determine the age of larva in queen grafting situations or to cause a break in the brood cycle without destroying a queen.

In making nucs and splits you may transfer frames that have queen cells on them. Other times you can cut the cells out of a frame for transfer or have the queen cells that have been developed from a specially designed queen cell base or cup. In hives where there might be many queen cells, a cell protector might be used until you put the cell where you want it to belong. Cell protectors have been made out of wire or plastic.

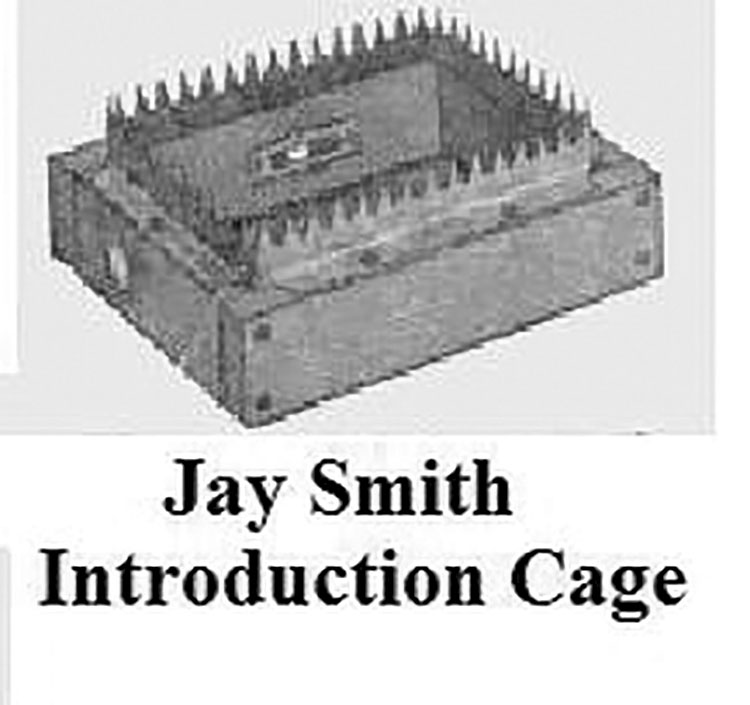

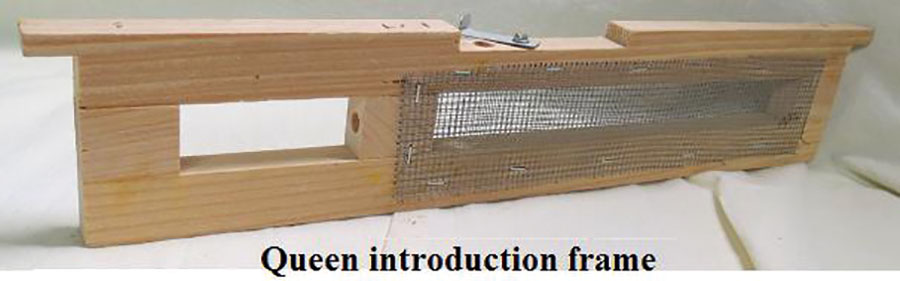

In difficult situations where you need more time for the bees to accept the queen or the weather has been inclement, there is an introduction frame available where you can insert a wooden mailing cage and let the queen be released into an area where she can be attended by the bees in the hive. After you feel that she will be accepted, you can open the release hole in the top of the frame. This idea is very similar to the Miller Queen Catcher and Introduction cage of the 1920s, but solves the problem of catching and handling the queen.

You can see that there are many options in introducing queens.

Many of the illustrations came from the 1920 and 1930 Root Catalogs.