As the Agriculture Department prepares for a majority of staff at two scientific agencies to quit rather than move to Kansas City later this year, it has begun asking retired former employees to return to work, either at USDA headquarters in Washington or from their homes.

The department plans to relocate the Economic Research Service and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture to Kansas City by the end of September. Although employees have until Sept. 26 to make a final decision about whether to accept relocation orders or leave the agency, a majority at both agencies thus far have declined to move.

Facing the prospect of a mass exodus, the department has begun offering jobs to retirees from the two agencies under a waiver from the Office of Personnel Management that allows retired federal workers to return to work while still receiving their defined benefit annuities.

One former ERS employee, who retired several years ago, told Government Executive that the department offered a position working 20 hours per week, at the same salary—prorated on an hourly basis—they were making before they left the agency.

“They offered me a chance to come back 20 hours a week at half of my full salary to work between now and the end of the year in whatever office space they can find in the South Building [of USDA Headquarters],” the former employee said. “Then after that, we would work [entirely] from home.”

The former ERS employee was told by colleagues that none of ERS’s current employees responsible for editing reports before they are published have accepted relocation orders. Even if the department hires a new cadre of workers for those positions, the employee feared the turnover could cause major problems for the agency.

“These reports are very dense, and as an editor you go back and forth with the economists a lot,” the former employee said. “It’s like editing a legal document—you have to get the exact verb correct, and you often can’t edit sentences the way you would other documents. There’s going to be a big ramp-up time to get people who edit these reports up to speed.”

In a statement, a USDA spokesperson confirmed that the department would use the Reemployed Annuitants program to “maintain continuity” at ERS and NIFA following the relocation to Kansas City. The department did not answer questions regarding how many retirees it hopes to rehire or whether any editors have agreed to move to Kansas City.

“Utilizing reemployed annuitants is one component of the department’s long term strategy to maintain the continuity of ERS and NIFA’s work,” the spokesperson said.

Under the retired annuitant program, an agency can hire former federal workers to one-year term positions, which can be extended. A worker hired under this authority would be paid their full salary and still receive their full retirement payments.

Both the former employee and Peter Winch, special assistant to the national vice president of the American Federation of Government Employees, who has represented ERS and NIFA employees since they voted to unionize earlier this year, said that ERS is planning to offer retired annuitant status to employees who accept Voluntary Early Retirement Authority payments rather than relocate to Kansas city.

“I can confirm that Dr. [Scott] Angle at NIFA specifically said that NIFA would be planning to rely on reemployed annuitants as well as contractors and new hires to cover the mass attrition,” Winch said. “We asked about it because ERS had mentioned retired annuitants in an earlier meeting. The impression we got at ERS was that the reemployed annuitants might be people who retired some time ago, as well as those leaving payroll now, and that, ironically, they might be allowed to work remotely from the D.C. area.”

Steve Crutchfield, who served as assistant administrator of ERS from 2007 until he retired in 2016, said that even if the department is able to temporarily cover for its workforce losses through contractors and rehiring retired employees, the loss of institutional knowledge will have a severe negative impact on policymaking and the agricultural industry.

“One of the experts that I relied on for issues of farm structure competition and concentration, he’s leaving,” Crutchfield said. “He was the person I’d go to and say, ‘Help, I need an answer and I need it right away.’ If I were there today, I don’t know how I’d be doing my job. So many people with so much expertise and knowledge are not going to be there. It takes years; it takes a long time to build up the intellectual capital to be able to answer the questions I had to answer [from stakeholders].”

Crutchfield said he was frequently a liaison between ERS and other agencies, as well as policymakers on Capitol Hill. He said that lawmakers, state and local governments, as well as the agricultural industry and investors in commodity markets all relied on ERS reports, which run the gamut from farm income forecasts to analyses of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

“I think [the staff turnover] is going to be deleterious,” he said. “The information is not going to be as complete, not as comprehensive. On the commodities side, because I’m not at ERS anymore I can’t speak to whether they would drop coverage of the commodities, but it might mean that forecasts might come out less frequently. I’m also hearing that USDA is cutting back on some of its surveys, and without the underlying data to work with, how are analysts going to be able to answer these questions and put out these reports?”

Crutchfield said, given his experience as the main point of contact for people outside of USDA looking for information from ERS, he does not believe Secretary Sonny Perdue’s stated goal of moving the agency “closer to its customers.”

“The customers of ERS’ work to a great extent, where it had the greatest impact, was decisionmakers in Congress and in the executive branch offices,” he said. “I can say I very rarely got a call from a farmer out in the Midwest asking a question.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

University of Guelph researchers in Canada have discovered at least one species of ground-nesting bees is being exposed to lethal levels of neonicotinoid insecticides in the soil.

They say this is important given the majority of bee species in Canada make their nests in the ground.

The first-ever study investigating the risk of neonicotinoid insecticides to ground-nesting bees focused on hoary squash bees, which feed almost exclusively on the nectar and pollen of squash, pumpkin and gourd flowers.

Researchers found the likelihood that squash bees are being chronically exposed to lethal doses of a key neonicotinoid, clothianidin, in soil was 36% or higher in squash fields.

This means 36% of the population is probably encountering lethal doses, which is well above the acceptable threshold of 5%, in which 95% of the bees would survive exposure.

“These findings are applicable to many other wild bee species in Canada that nest on or near farms,” says Environmental Sciences professor Nigel Raine.

“We don’t yet know what effect these pesticides are having on squash bee numbers because wild bees are not yet tracked the same way that honeybee populations are monitored. But we do know that many other wild bee species nest and forage in crop fields, which is why these findings are so concerning.”

The study , published in Scientific Reports, involved collecting soil samples from 18 commercial squash fields in Ontario. Pesticide residue information from these samples and a second government dataset from field crops was used to assess the risk to ground-nesting squash bees.

The research comes as Health Canada places new limits on the use of three key neonicotinoids, including clothianidin, while it decides whether to impose a full phase-out of these pesticides.

“Current risk assessments for insecticide impacts on pollinators revolve around honeybees, a species that rarely comes into contact with soil,” Raine says.

“However, the majority of bee species live most of their life in soil, so risks of pesticide exposure from soil should be a major factor in these important regulatory decisions.”

Only about 20% of the neonicotinoid insecticide applied to coated seeds is actually taken up into the crop plant; the rest stays in the soil and can remain there into subsequent seasons.

Squash bees are at particular risk because they prefer the already-tilled soil of agricultural fields for their elaborate underground homes.

As they build their nests, they move about 300 times their own body weight worth of soil. The researchers say it’s difficult to know exactly how much pesticide residue enters the bees. But they calculated that even if they are conservative and assume only 25% of the clothianidin enters the bee, the risk of lethal exposure in pumpkin or squash crops is 11% — still above the widely accepted threshold of 5%.

The team also examined the exposure risk in field crops, since many ground-nesting bee species live near corn and soybean fields, which use neonics as well. They found that 58% of ground-nesting bees would be exposed to a lethal dose of clothianidin while building their nests even if only 25% of the clothianidin in the soil enters the bee.

The researchers say pumpkin and squash farmers face a dilemma in that they want to protect pollinators, such as the squash bee, because they are vital to crop production, but at the same time need to protect their crops from pests.

“New approaches are needed that allow farmers to control pests and protect pollinators simultaneously,” they say.

“(The) advice to farmers is if you find an aggregation of squash bees nesting on your farm, protect these key pollinators from exposure to neonicotinoids by either not using them at all, or at least not using them near the aggregation. Creating pesticide-free places to nest will help your population of squash bees to grow over time.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

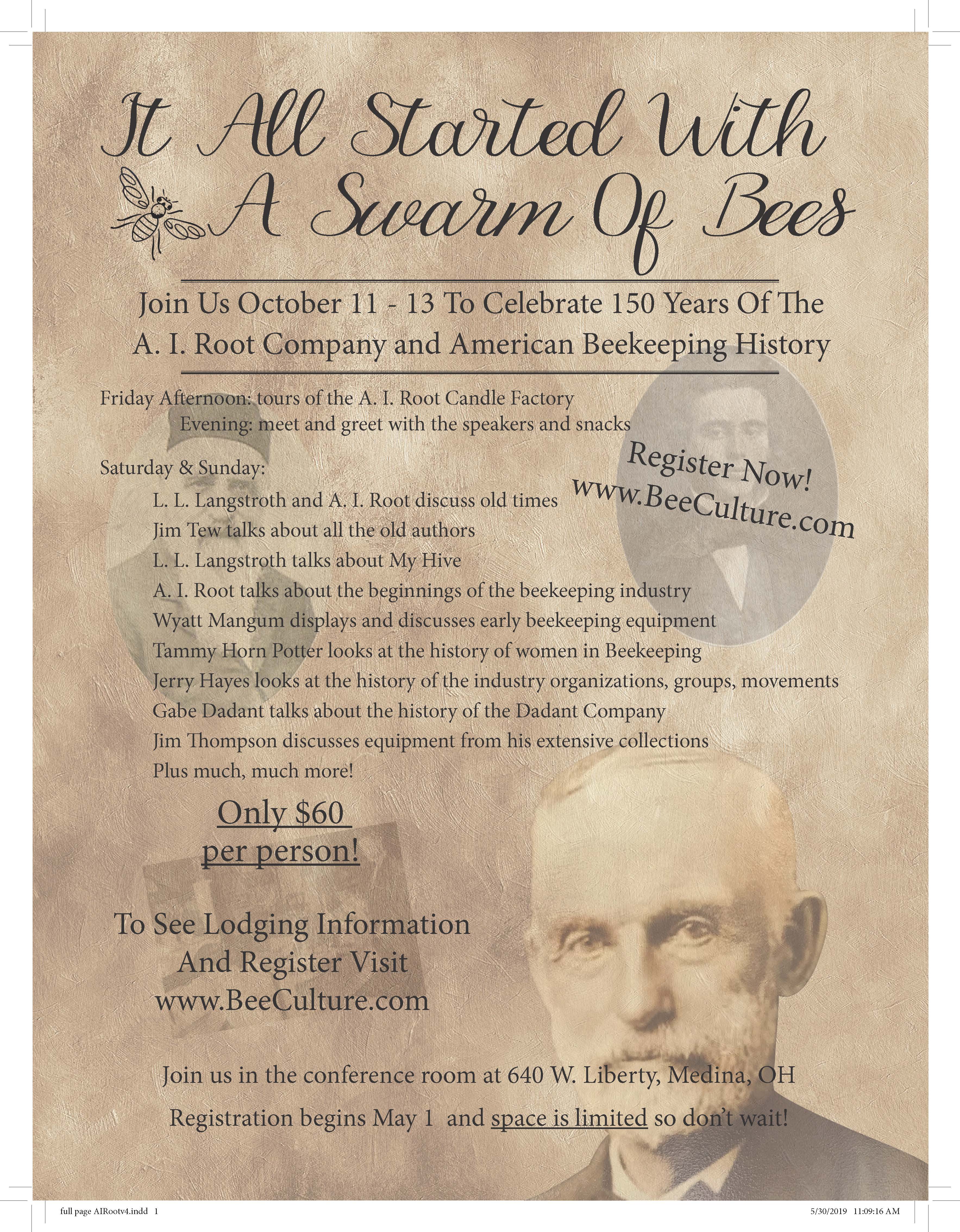

Don’t Delay – Register TODAY!!!