Ohio State Beekeepers Association, Tim Arheit, President; Terry Lieberman-Smith, Vice President; Michele Colopy, Treasurer; Annette Birt Clark, Secretary

The recent bee kill of honey bees in South Carolina due to a mosquito pesticide spray application is cause for concern of every beekeeper. The destruction of forty-three hives is not just a loss of honey bees, but their honey crop, the pollination of fall plants, and forty-three hives that would be available to pollinate crops next spring. The loss of forty-three hives to a beekeeper is a $21,500 cost to just replace the beekeeping equipment (now toxic from the mosquito spray) and to purchase new honey bees. This does not include the financial loss of the honey crop from this beekeeper’s livestock.

Mosquito control pesticide labels clearly state their toxicity to honey bees and other beneficial insects. However, the “public health exemption” allows mosquito control districts to apply these bee toxic pesticides against the label directions (spraying it on blooming weeds and crops, water, and during the daytime when bees are foraging). Communities are concerned with the “night-feeding” mosquito that carries West Nile virus, and now the “daytime-feeding” mosquito possibly carrying the Zika virus. However, we can protect pollinators and public health. We can reduce the number of mosquitoes, and reduce the use of bee toxic pesticides. Education and awareness is key. Mosquitoes typically feed within 300 feet to a maximum of one mile of their breeding area. If you are being bitten by mosquitoes, then you and your neighbors are breeding mosquitoes. To protect our bees and our health, we must all work to reduce mosquito habitat!

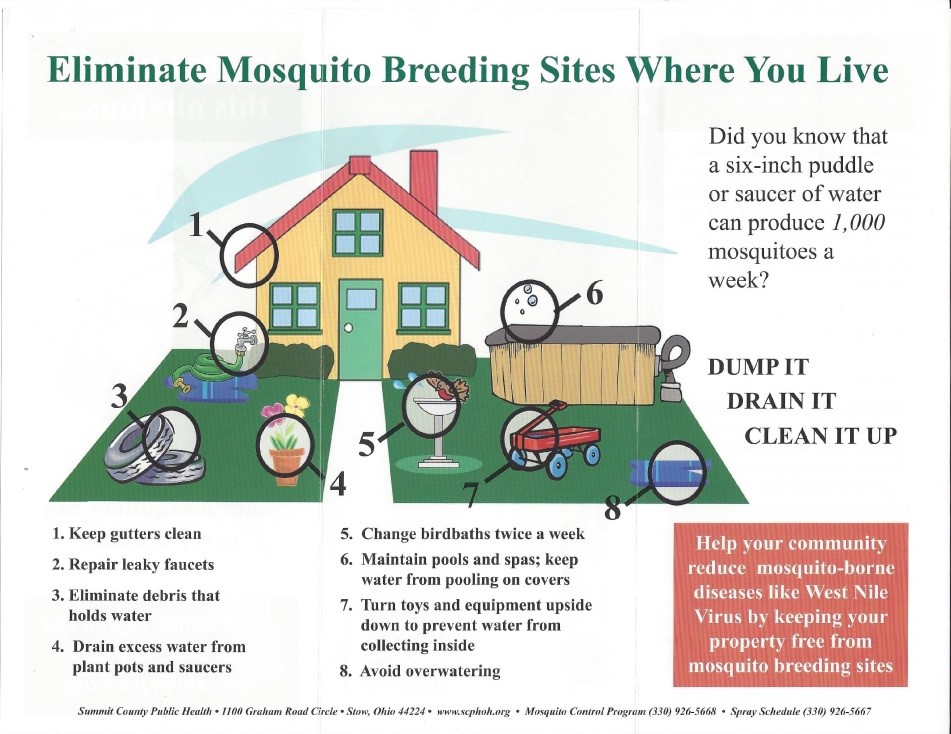

Individuals should remove trash and standing water on their own property in order to protect themselves and others from mosquitoes, and to reduce the use of bee toxic mosquito control products. The biggest battle is with individuals not taking care of their property. They expect a government mosquito abatement program to address nuisance mosquitoes, when it is only meant to protect public health. Mosquito populations would be greatly reduced if humans would eliminate standing water. A six inch puddle of water can produce 1000 mosquitoes a week. As beekeepers we want our honey bees to have access to pesticide-free water, as well as water free of mosquito larvae. But water is where it starts for mosquitoes. We can control for disease carrying mosquitoes, and the public can help to eliminate mosquito breeding areas.

The main aspect of a community Mosquito Control Program is surveillance. Traps placed throughout the community each day capture mosquitoes for testing, and to monitor mosquito population levels in that area. If populations are high and/or if disease carrying mosquitoes are found the local Health District will combat the mosquitoes with a larvicide, barrier treatment, and/or ULV spray applications (ultra-low volume).

Some cities offer beekeepers the opportunity to “opt-out” of mosquito spray applications near their property. Other communities provide a sign to post at each end of your property so county workers will not spray between the signs (your property frontage). However, a pesticide applicator will continue to spray before and after your property signs. Even if a beekeeper opts out of having their property sprayed for mosquitoes, pesticides drift onto water and blooming plants. Not all mosquito control products have a short residual toxicity, and can last more than eight hours on the blooming plants and in water. The next day when bees drink from a puddle or stream, or collect nectar from a bloom containing a mosquito control pesticide, the honey bee or native pollinator may die.

Many mosquito control products address mosquito larvae in water, and then imply the pesticides in the water will not harm bees. Bees do drink water. If a pesticide lingers in the water, bees will encounter the pesticide there, as well as on blossoms, and guttation droplets on plants. Honey bees, and native pollinators need access to clean water. Far too many mosquito control documents ignore the fact bees drink water, and mislead the pesticide applicator stating bees stay in their hives after 3 p.m. Many university extension documents and state guidelines claim bees are not active after 3 p.m. which is just blatantly false. Honey bees and native pollinators will forage blooming plants until the sun sets. To fully protect honey bees and native pollinators from mosquito control pesticides, the pesticide should only be applied when it is dark. Dark is dark: not twilight, not sunset: dark.

Every living creature needs clean, pesticide free water to drink; and “busy as a bee” means on warm, hot days honey bees work from sunrise to sunset, and they need water to cool the hive, and themselves. Changing water daily in bird baths provides clean water for bees and reduces mosquito breeding grounds. For water features like fountains and small ponds make sure that water is moving or contains aquatic life that will eat mosquito larvae, again reducing mosquito breeding areas.

A public health emergency allows for the exceptions to the label directions to occur and application of the product made against the label protections for pollinators. Communities must ensure they are truly protecting human health. Ask your local Health Board if they are trapping and testing mosquitoes for disease. If diseases are not found in mosquitoes, then tax dollars should not be wasted applying a pesticide when it is not needed. Prophylactic use of pesticides is as problematic as prophylactic use of pharmaceutical drugs. Regular use depletes their ability to work.

We can protect human health, and we can protect honey bees. Beekeepers should be able to protect their honey bees from mosquito control products. As a community we should protect our native pollinators. As individuals we can be proactive to protect our property from mosquitoes, and protect our honey bees and pollinators from the adverse impact of mosquito abatements. If a health risk is found in trapped mosquitos, a short residual toxicity mosquito control product should only be applied after the sun has set, when it is dark. Only then will honey bees and native pollinators have a chance to survive mosquito abatements.

As beekeepers become involved with their State Pollinator Protection Plans, we must make mosquito control programs part of Pollinator Protection Plans. We must all work together to ensure our beneficial insects are available to pollinate our backyard gardens, city parks, and Community Supported Agriculture. We must work together to protect ourselves from mosquitoes, reduce the breeding grounds of mosquitoes, and protect pollinators.

Ohio State Beekeepers Association

Tim Arheit, President

Terry Lieberman-Smith, Vice President

Michele Colopy, Treasurer

Annette Birt Clark, Secretary