By: Jay Evans

NEXTEST-GENERATION SCIENTISTS

I am a bit of a cynic for fairs and award shows (and don’t get me started on beauty contests), but I was deeply moved by the energy and insights provided by high school students from 81 countries at this month’s Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (https://student.societyforscience.org/intel-isef). When my daughter Simone was invited to compete I wasn’t sure it would merit spending a week in Pittsburgh (and yes I did joke that the second-place Maryland girl received TWO weeks in Pittsburgh), but fortunately Simone pushed, and off we went to the ‘Olympics’ of youth science.

The Fair included about 20 presentations related to pollination, and I tried to visit all of them. One favorite was presented by Elizabeth Wamsley from Timber Ridge Scholars Academy in Missouri. Elizabeth used RNA interference to target Varroa mites, a hot topic both in industry and at research labs, including ours. She was able to see an effect of RNA knockdowns after soaking mites in solutions containing RNA segments targeting Varroa mitochondrial proteins, broadening the list of potential mite targets. Elizabeth won scholarship offers and cash awards for her efforts.

Natalia Jacobson from Empire High School in Arizona also focused on a major honey bee health threat, in her case Nosema disease. Natalia provided new insights into the impacts of protein nutrition on Nosema. Specifically, by supplementing diseased bees with the amino acid cysteine, she measured increased immunity and survival along with the enlarged hypopharyngeal glands typical of healthy bees. As with other emerging research, “your results may vary”, so please hold off on introducing cysteine into your colonies until more work is done. Still, Natalia’s project and analysis were careful and the results are truly exciting.

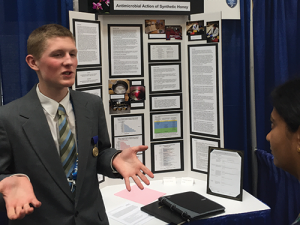

On the medical side, William Deering from IDEA Homeschool in Alaska tested whether plant compounds added to a ‘synthetic honey’ comprised of sucrose syrup could lead to new antibiotics. After informing him of the unfortunate connotations of the term ‘synthetic honey’, I leaned in to see which compounds he favored and to compare them to similar ongoing efforts aimed at bee health. William found that infusions based on extracts from Alaskan flowers led to lower bacterial growth in 16 out of 17 cases, indicating a wide potential for plant extracts as a new source of antibiotics. He is widening his scope to plant extracts from other parts of North America and beyond, and has the energy to really ramp up this search.

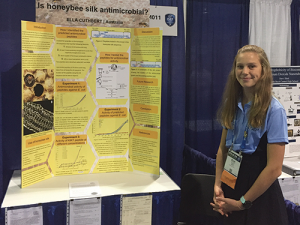

Also in the ‘what can bees do for you?’ section, Australian student Ella Cuthbert (Lyneham High School) had a brilliant project looking at medical uses for honey bee silk. To avoid some extremely tedious collections, she inserted the major silk proteins into a laboratory production system, allowing her to make these proteins in a test tube. In the end, two silk proteins were shown to reduce the growth of bacteria. Combined with the strength characteristics of silk, this finding might lead to new wound dressings. Nobody defines youthful optimism better than Ella, who started her abstract with “The dream of living forever, only accomplishable by replacing broken parts of the human body, is closer than it has ever been before.” Take THAT, curmudgeons.

Additional international entries came from Thailand (A New Method to Increase Propolis Production by Activating Nest Repair Behavior in Stingless Bees), South Africa (Determining the Availability of Pollen Sources for Honeybees on Deciduous Fruit Farms in Summer), and Puerto Rico (Comparative Study Between Bellis sylvestris, Artemisia dracunculus and Lantana trifolia in the Ability to Attract Apis mellifera). These entries, also, were well done and well presented.

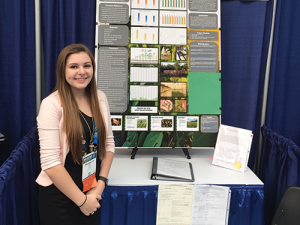

In the end, if I had to pick a ‘Best in Show’ it would go to Brooklyn Pardall from Central Lee High School in Iowa. Brooklyn showed a stunning increase in soybean yields when honey bees were part of the picture. Honey bees are not needed for soybean production, since production soy plants are self-pollinating, nor are bees really thought to crave the rewards provided by soybean flowers. Nevertheless, having hive boxes amidst rows of soybeans seems to have increased yields by over 20%. This is a huge margin in a crop already pushed to production capacity. What gives? It could be that bee visits tap into a dormant plant reproductive cue, even when the pollen they deliver is no longer critical. In a similar vein, asexual coffee plants were shown by Smithsonian scientist David Roubik to respond favorably to honey bee visits, increasing bean yields substantially (https://www.nature.com/articles/417708a). Brooklyn is planning follow-up experiments this year. Having met her and her team, and knowing that she carried out all of her experiments on her own family’s 6,000 acre soybean farm, I would not bet against her. If it turns out that honey bees significantly improve soybean crops, this could be a three-way win; better crop production, a new revenue source for beekeepers, and a stronger incentive for soybean farmers to maintain a healthy environment for visiting pollinators.

Since I don’t have a gig at a plant magazine, I can’t give much space to Simone Evans’ awesome orchid project nor her success at these Olympics, but she already knows who’s the favorite – and despite my snarky comment at the start, Pittsburgh was really fun. It reminded me of the 1970s and 80s Seattle of my youth, before that city became so sparkly. If you are able, I would strongly recommend attending the public days at INTEL/ISEF in the future to see some great ideas and outputs (Phoenix in 2019, Anaheim in 2020). You can also peruse projects from this year and many former years at https://abstracts.societyforscience.org/. Many past competitors continue to have a great impact on the field. Regardless, please support your local science students, relatives or not, as they set out on ways to improve the world.

Jay Evans is the Research Leader for the USDA Honey Bee Lab in Beltsville, MD.