Nitrogen Crisis From Jam Packed Livestock Operations has Paralyzed Dutch Economy.

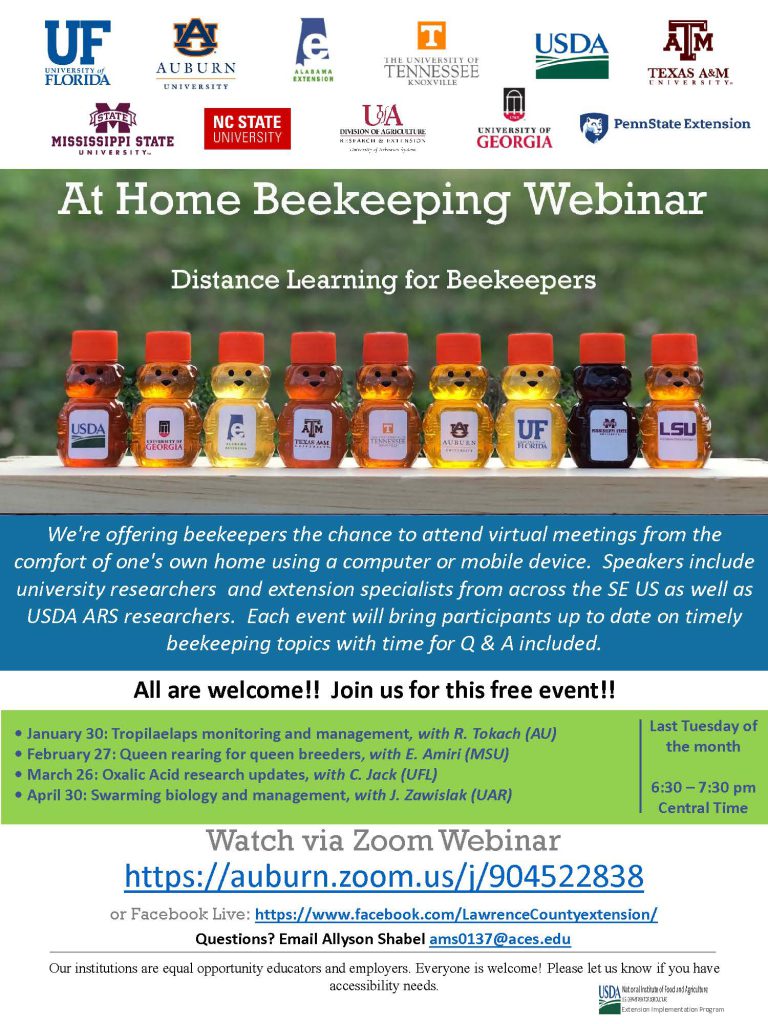

Dutch farmers have protested a ruling that curtails the expansion of livestock operations because of the nitrogen pollution they produce. VINCENT JANNINK/ANP/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

By: Erik Stokstad

Last week, Dutch farmers across the country parked their tractors along highways in the third such protest since October, when they jammed traffic while driving en masse to The Hague, the nation’s center of government.

They are protesting a Dutch high court decision that in May suspended permits for construction projects that pollute the atmosphere with nitrogen compounds and harm nature reserves. The freeze has stalled the expansion of dairy, pig, and poultry farms—major sources of nitrogen in the form of ammonia from animal waste. Also blocked are plans for new homes, roads, and airport runways, because construction machinery emits nitrogen oxides. All told, the shutdown puts some €14 billion worth of projects in jeopardy, according to ABN AMRO Bank. “It has really paralyzed the country,” says Jeroen Candel, a political scientist at Wageningen University & Research.

The government is preparing to enact short-term measures, including lowering a highway speed limit, which could reduce nitrogen emissions a sliver. To make a significant dent, many experts say the country’s farm animal sector—the densest in the world—must shrink and recycle more of its nitrogen. Last month, farmers asked for nearly €3 billion over 5 years to help pay for more environmentally friendly ways to deal with manure. Although agriculture is a large source of nitrogen emissions, other sectors will have to rein in their pollution, too. “Those are really tough political decisions that have to be made,” says Jan Willem Erisman, a nitrogen expert at the Louis Bolk Institute in Bunnik.

Nitrogen, a key nutrient for plants, is also an insidious pollutant. Fertilizer washing off fields ends up in lakes and coastal areas, causing algal blooms that kill marine life. Airborne nitrogen can also harm ecosystems. One source is nitrogen oxides, mostly from power plants and engine exhaust. In the Netherlands, even more comes from the ammonia vapors from livestock urine and manure. Both kinds of nitrogen react to form aerosols that cause smog, damage foliage, and acidify the soil, hindering roots’ absorption of nutrients. (Dutch farmers must add lime to their fields to fight acidity.)

The Netherlands is a nitrogen hot spot partly because it is a dense, urbanized nation, although controls on power plants and catalytic converters in autos have helped curb nitrogen oxide emissions. The bigger problem is ammonia emissions from concentrated livestock operations. Dutch farms contain four times more animal biomass per hectare than the EU average. Practices such as injecting liquid manure in the soil and installing air scrubbers on pig and poultry facilities have reduced ammonia emissions 60% since the 1980s, but they have risen slightly since 2014 because of expanding dairy operations. Dutch agriculture is responsible for nearly half of nitrogen pollution that falls in the country.

In 118 of 162 Dutch nature reserves, nitrogen deposits now exceed ecological risk thresholds by an average of 50%. In dunes, bogs, and heathlands, home to species adapted to a lack of nitrogen, plant diversity has decreased as nitrogen-loving grasses, shrubs, and trees move in. Heathlands are turning green-gray as invasive grasses overwhelm the purple heather and yellows and blues of small herbaceous flowering plants, says Eva Remke, an ecologist at B-WARE Research Centre in Nijmegen. “The grasses will win, and the herbs will lose.” These losses cascade through the ecosystem, contributing to the decline of insect and bird diversity, she says.

To control emissions, in 2015 the Netherlands introduced a nitrogen permit system that allows construction if, for example, regional governments reduce nitrogen from other sectors, such as farming. The system relies on a model developed by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) to calculate how much nitrogen is emitted by various activities and how much they contribute to pollution in natural areas.

The system was not enough to satisfy environmental groups. They sued the Dutch government in 2016, demanding that it deny construction permits for expanded animal operations near two nature reserves. The cases ended up in the Court of Justice of the European Union, which last year ruled against the government and criticized the permit system for not ensuring immediate nitrogen reductions.

The Dutch high court implemented the ruling in May, halting all permit applications. It said the government needed to come up with a better system and a long-term plan to reduce nitrogen emissions. In September, a high-level commission suggested some short-term fixes, which the government has asked the high court to review. One idea is to lower the daytime speed limit from 130 to 100 kilometers per hour, which would reduce emissions enough to restart some home building. (The entire construction sector contributes just 0.6% of nitrogen emissions.) The government also wants to require changes in animal feed that would reduce nitrogen levels in manure and to buy out some farms near nature reserves. But the commission warned that deeper emissions cuts would require hard choices.

Some scientists and environmental groups say the Netherlands should move to circular agriculture: Farms should only produce as much manure as they can use to fertilize nearby fields; cows should graze rather than be fed nitrogen-rich, imported soy; and pigs and poultry should eat food waste. That would mean 50% fewer animals, says Natasja Oerlemans, head of agriculture for the World Wildlife Fund–Netherlands in Zeist. “We should use this crisis to transform agriculture,” she says, adding that it will require several decades and billions of euros to reduce the number of animals.

LTO Netherlands in The Hague, which represents 35,000 farmers, endorses the concept of circular agriculture, but cautioned against “hasty measures.” One new grass-roots group, the Farmers Defence Force, contests the RIVM model’s calculations of how much nitrogen from farms is deposited on nature reserves. RIVM has defended its model, which was peer reviewed before its 2015 launch. But it will ask an external committee to review both the model and the national nitrogen monitoring network.

Candel thinks EU courts might impose similar decisions on other European nations in the future. But for now, Dutch farmers will likely face tougher nitrogen restrictions than those in neighboring countries. That will rankle, especially because cross-border pollution is part of the problem, says Wim de Vries, who studies nitrogen impacts at Wageningen. About one-third of the nitrogen pollution deposited in the Netherlands comes from other countries, he says. “Nitrogen spreads everywhere.”