A Comparison Of Different Methods Of Obtaining Honey Bees

By: Patrick Dwyer

Making increase is a fundamental activity of beekeeping whether one is a beginner beekeeper who purchases her first bees, a more experienced beekeeper who wants to replace lost colonies, or an established commercial beekeeper who proactively expands the number of colonies.

There are a number of ways to accomplish this end and this article will discuss six of these methods that are utilized to support successful beekeeping.

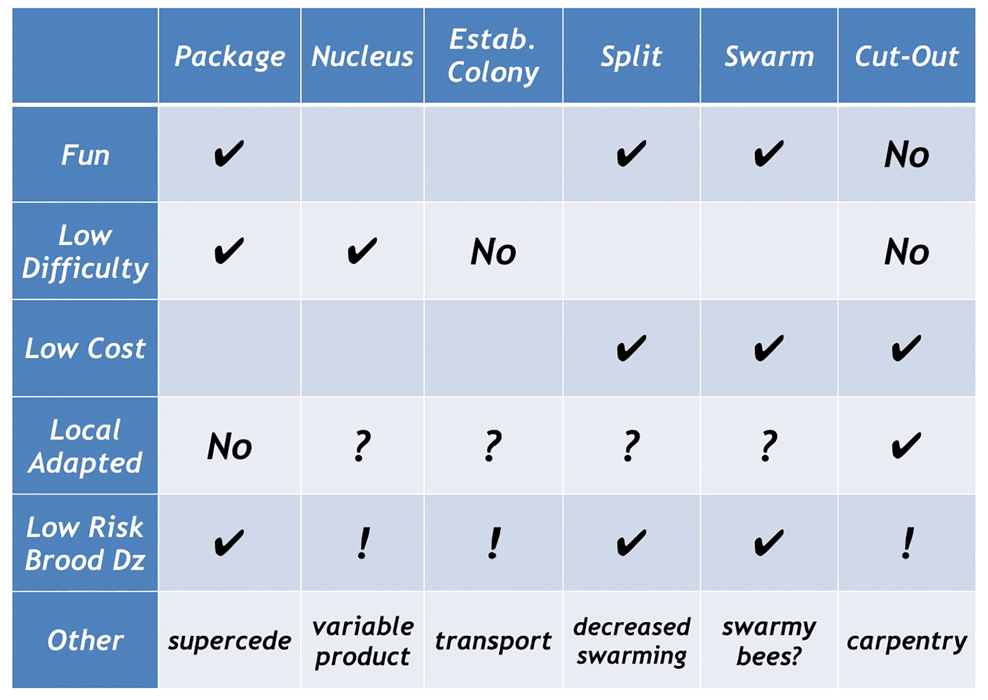

The methods to be discussed include purchasing package bees, nucleus colonies, or established colonies as well as creating splits, performing swarm capture, or doing removals. For each method we will briefly define it and explain how it is performed and then focus on a systematic comparison with the other methods. Comparisons will include weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each including each method’s “fun factor,” difficulty, cost, as well as the contribution of other factors such as queen quality, local adaptability, transmission of diseases and pests, Africanized genetics, feeding requirement, possibility of surplus honey production, and others. I hope that this comparative analysis of increase methods will be of interest to both beginner and experienced beekeepers.

Package Bees

A package is a collection of several pounds of honey bees from multiple donor colonies shaken into a screened box without associated frames, combs, or brood but with an unrelated queen in a separate cage. Packages are generally produced in warm climates in the spring and can be shipped through the U.S. Postal Service or picked up at regional locations. Packages were a major method for increase in the 19th and 20th centuries including for Canadian beekeepers before the honey bee importation ban.

Installing package bees involves preparing a single story hive generally containing foundation, shaking the bees into the hive with a feeder, and allowing for the release of the queen after a brief period of introduction.

Advantages include a high fun factor as a beekeeper is able to observe all new colony activities including comb building, egg-laying, brood development, and the storing of nectar and pollen. At the outset this is a small colony that is easy to manage and ideally suited to beginners. The difficulty of installation is actually quite low, queen quality is generally quite good with a young, prolific queen, and transmission of brood disease is not seen.

Disadvantages include a significant cost (generally $90-140) and the fact that local adaptability is absent unless one’s apiary is in a region producing packages and this contributes to a reputation of variable Winter survival. Transmission of pests might include small hive beetles and Varroa, Africanized genetics may be carried by these bees when shipped from certain regions, and these colonies generally have a feeding requirement for sugar syrup when installed. Production of surplus honey is uncommon during the first year unless packages are installed on drawn comb. Other factors include a significant risk of supercedure during the first year, infrequent problems with acceptance of the introduced queen, and the requirement to learn how to install the package but this is relatively easy for even beginners to perform.

Package bees always come from warm climates but beekeeping vendors and bee clubs are a source of these bees or they may be directly purchased through the mailfrom sellers.

Nucleus Colony

A nucleus colony (“nuc”) is a small established colony generally with four to five frames of drawn comb containing brood, honey, pollen, and empty space for egg-laying, worker bees, and a queen. Nucs were an important in-apiary resource for Langstroth and Brother Adam and have become an important method of increase during the past quarter century.

Installation of a nuc into a standard hive is straightforward only requiring the transfer of combs and bees from the nucleus colony to the recipient hive generally with a feeder and frames of foundation.

Advantages include that the difficulty of installation is extremely low, queen quality should be good with a young prolific queen or an overwintered “tested” queen, and local adaptability could be a plus with locally sourced queens. A nucleus colony might produce surplus honey in the first season if it is installed in a standard hive early in the season particularly with drawn comb. As a nuc is already an established colony there are no problems with queen acceptance with this method.

Disadvantages include that the fun factor of installation is low, the cost is high to very high ($125 to over $200 for a “tested” nuc), and local adaptability may be unexpectedly absent even when purchasing from local beekeepers as nucleus queens are commonly reared in regions remote from where local nucleus colony sellers are located. Whenever used bee equipment is sold (such as with frames in a nucleus colony) there is a risk of transmission of brood disease, nucs also have a risk of transmission of pests including Varroa and small hive beetles, and nucleus queens from regions with Africanized genetics can also carry these. Surplus honey will not be obtained with small nucs and those installed late in the beekeeping season or on frames without drawn comb. Other disadvantages include that nucs are frequently a variable product that may contain old and damaged frames, new foundation, an old queen, a queen introduced just prior to sale, or no queen at all and nucs have a reputation as a method for unscrupulous sellers to unload unwanted combs from their operation.

Nucleus colonies can be obtained from many regional beekeepers and one should always ask about the quality of the product from trusted beekeeping contacts and consider asking an apiary inspector about disease issues.

Full-sized Colony

A full-sized colony is generally a single or double deep established colony containing drawn comb, brood, honey, pollen, bees, and a queen with complete hive equipment including bottom board, hive bodies, and top cover.

Installation of a full-sized colony involves moving it to a desired permanent location and in the absence of heavy equipment requires some heavy lifting.

Advantages include that a locally sourced product could have local adaptability with a regionally reared queen, a low risk of Africanized genetics if located outside of a region with such genetics, generally the absence of a feeding requirement, a colony that is ready for surplus honey production in its first season, and other factors such as a ready pollination resource and the provision of full hive equipment.

Disadvantages include a low fun factor and a moderately high difficulty because of problems inherent in moving a large and heavy colony as well as issues for beginners such as difficulty finding the queen and the intimidation of learning from a large colony. The cost is higher than that of a nucleus colony, queen quality is commonly suspect with an older, less prolific queen, and local adaptability may be lacking depending on the source of the seller’s queens. There is also a real risk of transmission of diseases and pests including brood disease, Varroa, and small hive beetles. Other factors could include poor condition of hive equipment.

Full-sized colonies may be obtained from retiring beekeepers whose reputation for disease management is known with certainty and can also be obtained from almond pollinators after almond pollination is completed.

Split (Divide)

Splits, or divides, are the product of splitting or dividing an established colony into several colonies. Although such daughter colonies can make their own queen splits generally use a queen cell or mated queen. Splits have been an important in-apiary method of increase for established beekeepers for more than 150 years.

There are many procedures for performing splits including a “walk-away” split by dividing a populous colony with ample resources into two with eggs and larvae in both parts or more generally using a new queen in splits containing two to four frames of brood of all ages with covering nurse bees from a strong colony or several colonies.

Advantages of splits include a moderately high fun factor and low cost ($0 to $50). Queen quality can be a focus of this method with a young, prolific queen, associated expected good winter survival, and the option of using hygienic or other pest-resistant queens or with queens with demonstrated local adaptability from regional queen breeders or one’s own apiary. When using one’s own frames for split creation the risk of transmission of diseases and pests is exceedingly low, in fact with predictable reduction in Varroa by dilution, out-competition by the explosive brood-rearing that follows splitting, and interruption of the brood cycle particularly when using queen cells. One might produce surplus honey in the first season if splits are well-provisioned (including with drawn comb) and created early in the season. Other favorable factors include decreased incidence of swarming in colonies donating combs to splits, probably fewer Winter losses, and the development of a self-sufficient sustainable apiary.

Disadvantages include that the difficulty of making splits is moderate for beginners and if using grafted queens from one’s own apiary can be technically challenging even for experienced beekeepers. Queen quality issues include that an introduced queen might not be accepted, a potential for poor queen-rearing conditions particularly for “walk-away” splits, and questions about possible lower Winter survival if using one’s own queens. Local adaptability might be an issue if purchased queens are not regionally derived, Africanized genetics could be introduced if queens are obtained from regions with those genetics, there is generally a feeding requirement for producing splits, surplus honey would not be expected unless an early-created split is well provisioned, and an other factor is that one should already have strong colonies to create splits limiting the application of this method to established beekeepers.

The source of inputs for splits generally include one’s own bees and brood either with queen cells (including those produced by the beekeeper) or mated queens the latter of which are shipped from many suppliers or may be available locally.

Swarm Capture

Swarm capture as an increase method consists of capturing a swarm of bees when they first alight at their bivouac site or by placing a “swarm trap” (“bait hive”) most commonly near one’s own apiary or a source of feral survivor bees. Swarm capture is the oldest method of increase with skep and gum beekeeping dependent upon it.

If obtaining a swarm from a bivouac site where a swarm has temporarily landed, the swarm is generally shaken into a container and then poured into the new hive or on a bedsheet surrounding the hive and then fed with sugar syrup. If using a swarm trap a box is placed in an area near managed or feral colonies. Generally the beekeeper assures that the box has a size, location, orientation, odor, and other qualities that are attractive to bees as a nest site.

Advantages of swarm capture include an extremely high fun factor with gentle bees and the observation of all colony activities. The cost is free, the bees might have local adaptability if they are cast off of locally adapted bees, and there is no risk of transmission of brood diseases. An other favorable factor is that these bees are generally productive builders of new comb on provided foundation.

Disadvantages include moderate difficulty for beginners in hiving a swarm, the possibility of poor queen quality with an older, less prolific queen in primary swarms, and the possibility of poor local adaptability if the swarm is obtained near a commercial apiary or beeyards with queens imported from other areas of the country. A feeding requirement is expected for these excellent comb builders and surplus honey production cannot be relied upon in a swarm’s first season. Other unfavorable factors include the possibility of selecting for “swarmy” bees, the difficulty of predicting when swarms will occur, poor Winter survival with late season swarms, and the risk of injury when retrieving swarms from sites not near the ground.

Swarms can be the products of one’s own or others’ apiaries, locations near feral survivor colonies, or beekeepers can publicize their willingness to serve as a community resource to retrieve swarms.

Removal (Cut-out)

Removals (cut-outs) of bees from a cavity in structures such as a house or barn or from a bee tree are also a method to obtain bees.

The procedure of doing a “removal” involves exposing the colony nest, removing the bees (sometimes with a bee vacuum) and the comb, attaching the broken comb into foundationless frames, and placing them into a recipient hive.

Advantages include low cost with free bees and the possible expense of a new replacement queen ($5 to $30), a possibility of local adaptability of bees that might be considered “survivor stock”, and an other factor that beekeepers can charge for such removals and develop a potentially profitable business in doing so.

Disadvantages include that the fun factor is quite low (unless doing “bee lining”), the difficulty is quite high with significant time and labor involved, unanticipated carpentry challenges, and the potential for falls and power tool injuries. Queen quality may be poor with a generally older, less prolific queen and a significant possibility of requiring queen replacement. There is a significant risk of transmission of diseases and pests particularly for brood disease and Varroa and for this reason quarantine is considered important by many who perform cut-outs. Generally there is a feeding requirement for removals after being placed in new equipment, surplus honey is uncommonly obtained during the first season, and other potential problems include dealing with crazy comb, increased defensiveness, and liability issues when working on someone else’s property.

Referrals for removals are commonly obtained by word of mouth and by publicizing one’s willingness to do these with fire departments, contractors, foresters, and tree surgeons.

Summary

There are a number of ways of either obtaining one’s first bees or making increase in a beeyard including purchasing package bees, nucleus colonies, or established colonies as well as creating splits, performing swarm capture, or doing removals. Except for the creation of splits by those who do not currently have any bees any of these methods may be used depending on the assessment of the method’s relative merits by the beekeeper.

While I believe that the fun factor and low risk of transmission of brood disease should always be emphasized, for beginners I prioritize a low level of difficulty while for beekeepers with established colonies I prioritize low cost. Thus, I recommend beginners purchase package bees from a region without Africanized genetics or small hive beetles and learn from these colonies. Nucleus colonies would also be very attractive for beginners if they were assembled by providers who are known to produce a high quality product, with locally adapted queens, and a high level of assurance that they are free of disease and pests. For beekeepers with established colonies splits are an ideal skill to make increase with one’s own or locally adapted queens or with queens imported for desirable hygienic or genetic traits. Swarm capture, particularly from one’s own apiary is also a cost effective way to make increase.