Auburn professors discuss causes of national decline in Apis mellifera honey bee colonies

Auburn professors discuss causes of national decline in Apis mellifera honey bee colonies

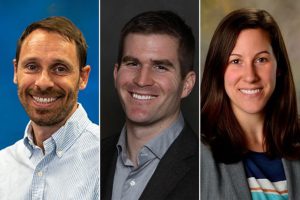

Auburn University professors, from left to right, Roberto Molinari, Geoffrey Williams and Stephanie Rogers were part of an international research team that studied the national and global decline of the Apis mellifera honey bee colonies.

Apis Mellifera honey bees are important insect pollinators whose impact has environmental, ecological and economical ramifications across the world. Recent research shows that U.S. beekeepers experienced a 43% colony loss for the crucial winged insect between April 2019 and April 2020.

Auburn University faculty members Roberto Molinari from the Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Geoffrey Williams from the Department of Entomology & Plant Pathology and Stephanie Rogers from the Department of Geosciences were part of an international team of scholars who researched the phenomenon of honey bee colony loss occurring in the U.S. The group recently published findings from its study in “Scientific Reports” as part of a collection dedicated to insect decline and extinction. Here they discuss what elevated colony losses mean for the future, as well as discuss how their study can help beekeepers better manage their colonies moving forward.

What are the main drivers of honey bee decline?

Molinari: Honey bee colony loss is widespread across the U.S., although it varies considerably across geographical areas and seasons. It is never simple to determine what the drivers of a phenomenon are when you don’t have control over the way the data are collected. Nevertheless, we have the tools to study potential links between stressors and honey bee colony loss over a period spanning from 2015-21. In this perspective, several stressors, on their own and also considered jointly with other drivers, appear to contribute to losses. Among them, Varroa destructor parasitic mites, pesticide exposure and extreme weather events (such as extreme temperature and precipitation events) appear to be the main drivers.

What do scientists know about the varroa mite, and what can be done to combat them?

Williams: The Varroa destructor mite parasitizes western honey bees in nearly every corner of the globe. Both beekeepers and scientists state that it represents a serious challenge for honey bees because it feeds on individual bees; this can result in a compromised immune system and the transfer of virsuses. Although much effort has been placed on better understanding and managing varroa, beekeepers still lack sustainable tools to reduce its effects. By taking a national approach, our study confirmed that varroa mites are a major driver of honey bee colony loss in the U.S., but also highlighted regional differences in varroa populations that may help beekeepers better prepare for the mite moving forward.

What role does environment and climate change play in this troubling trend?

Rogers: We found strong evidence across the U.S. that overwintering is the most crucial period of the year for colony loss, but some areas are more strongly affected than others. This finding actually confirms and supports evidence from another recently published paper that we developed in parallel to this work and that was specifically focused on environmental drivers. These results can be used to develop regional best-management practices to assist at-risk beekeepers in being better prepared for winter. While longitudinal data at much finer spatio-temporal resolution will be needed to fully understand the role of extreme weather events linked to climate change on honey bee colony loss, our results do provide some important preliminary insights, including the increased risk of loss linked to extreme events.

Which methods were used to collect data for this study, and what were your goals for teaming together for this research project?

Molinari: The challenge of this study was aggregating data from different open data sources which were collected at different spatio-temporal resolutions from different institutions. Adopting statistical techniques that enabled us to limit the loss of information, we aggregated these data together to obtain a good picture on the status of managed honey bee colonies, the stressors affecting them and the weather and land use conditions across the United States—over a period spanning from 2015-21.

Once the data processing was finalized, we adopted some state-of-the-art statistical modelling tools to determine the strongest statistical predictors removing the effects of different outlliers and forms of data contamination. This is the first study that has sought to understand honey bee colony loss across the U.S. using open-source data and controlling for different potential predictors. With this interdisciplinary approach, we hope our study will motivate efforts to collaborate across disciplines to tackle this multifaceted problem from many angles. Additionally, we hope these results highlight the need to increase both data collection efforts and data availability to researchers in the U.S., as well as other regions of the world.

Why is this study and this work so crucial to the understanding trends regarding the country’s honey bee population, and how widespread was your collaboration?

Williams: Understanding honey bee colony loss is so important because these bees are crucial pollinators of many agricultural crops, especially here in the U.S. Crops like almonds, blueberries, apples and even carrot seed all rely on honey bees for pollination. What’s novel about our study on honey bee colony health in the United States is its scope—we included data collected over several years and from most parts of the contiguous United States. By collaborating with researchers here at Auburn, the United States and Europe, we were able to shed light on the role of both biotic and abiotic threats.

It also was really encouraging to see such exciting science produced by outstanding young researchers collaborating across the Atlantic and connecting Auburn University and Pennsylvania State University to the University of Geneva (Luca Insolia), the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies (and its EMbeDS Department of Excellence) in Italy (Francesca Chiaromonte, also professor at the Pennsylvania State University) and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (Martina Calovi).

The Expert Answers Q&As and columns reflect the expertise and opinions of individual faculty members and do not necessarily represent an official policy or position of the university.

To arrange an interview with our experts, contact Preston Sparks, director of university communications services, at preston.sparks@auburn.edu.

We are here to share current happenings in the bee industry. Bee Culture gathers and shares articles published by outside sources. For more information about this specific article, please visit the original publish source: Auburn professors discuss causes of national decline in Apis mellifera honey bee colonies