Do Pollinators Prefer Dense Flower Patches? Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No

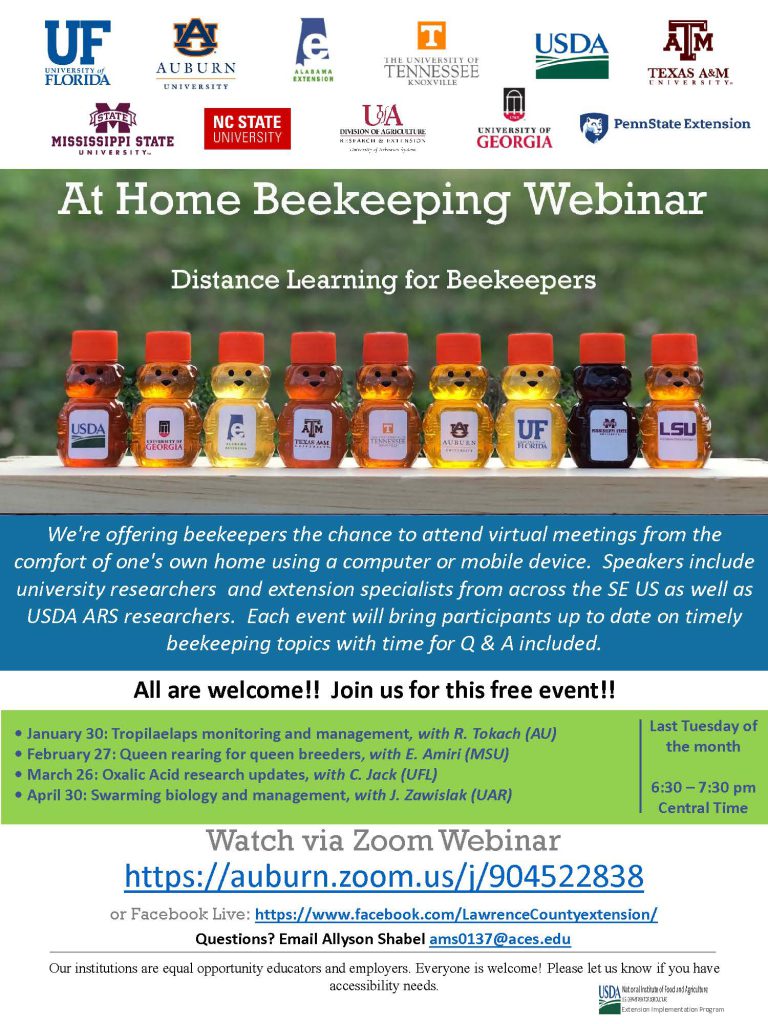

A study looking at floral density and pollinators finds that some types of pollinating insects prefer dense flower patches more than others, but that preference can also vary by flower species, too. The complicated findings offer clues to how multiple pollinator species co-exist and compete for floral resources. Shown here is a patch of Monarda fistulosa, one of the flower species included in the study. (Photo by Joshua Mayer via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

By Andrew Porterfield

Historically, entomologists have concluded that bees and other pollinators select flowering plants according to the density of those plants in a given location. This makes some economic sense, since foraging in large areas of the same flowers reduces flight time (and thus energy) between flowers.

But other research has shown that pollinator visits do not decrease when isolated from same-species plants, suggesting that flowers in dense formations compete for pollinators. Understanding how pollinators are attracted to plants is important to seeing how different species of bees can exist together in the same pollen-producing environment.

In a study published in December in Environmental Entomology, Tristan Barley, a student at Miami University in Ohio (now at the University of Illinois), and his colleagues found a large degree of variation in pollinator visitation when analyzed simply by density of flower patches. Instead, the type of flower appeared to have an effect on pollinator visitation, as did the type of pollinator.

In their study, the researchers looked at the effects of flower density on pollination in a restored Ohio prairie. They recorded visits to three plant species: Penstemon digitalis, Monarda fistulosa, and Eryngium yuccifolium. Pollinators were observed when they landed on a flower, foraged for flowers, or visited multiple flowers on the same plant. Pollinators observed included species of Bombus, Ceratina, and others.

The importance of flower identity over density, especially for Ceratina, was a surprise, Barley says.

“This group of pollinators was the only one to be a significant visitor for all three of our focal flower species, and yet flower-patch density affected their visitation rates in different ways,” he says. “When visiting Penstemon digitalis or Monarda fistulosa, both of which were also significantly visited by Bombus in our dataset, Ceratina tended to visit isolated flowers more often or even show no preference in patch density. However, the opposite was true when visiting E. yuccifolium. It seems that the identity of the flower being visited, as well as potentially the other pollinators visiting the flower, has an important effect on the patch-size preference in some bee species.”

For Bombus, the bees did seem to overall prefer larger flower patches. The authors note, however, that “nesting habitat may contribute to these findings, as Bombus species may preferential nest in higher density flower patches when compared with solitary bees.” It’s also possible that Bombus was reducing flight time and energy expense by visiting larger flower groups.

The biggest implication of their research, Barley says, is the possible mechanism bee species use to coexist in the face of varying densities of flowers. “Larger, more social bees, such as bumble bees, tended to visit larger flowering patches more than isolated flowers, whereas for smaller, less social bees, this was not the case,” he says. “Bumble bees may be outcompeting smaller bees in larger patches of flowers, but the smaller bees may be able to meet their energy needs through visiting isolated flowers instead.”

Because the researchers were studying only feral (native) bees in a non-agricultural plot of land, they were not able to determine the impact, if any, of Apis mellifera, the European honey bee. “Our results suggest that A. mellifera could compete more directly with Bombus species when they are present in a habitat, rather than smaller native bees,” which may avoid competition altogether, Barley says. But such interactions would only take place if honey bee colonies were deliberately placed near such a prairie.

This co-existence could help determine the extent to which pollinators could occupy a given area. The concept, Barley says, “to our knowledge, has not been fully explored, and it could help future researchers better understand how diverse bee communities can coexist despite sharing floral resources.”

Do Pollinators Prefer Dense Flower Patches? Sometimes Yes, Sometimes No (entomologytoday.org)