by Bee Culture Staff

Join Bee Culture Magazine’s Exploration of the Four Pillars of Honey Bee Management in October, 2015 at the Bee Culture Conference Center (on the A.I. Root Co. campus), 640 West Liberty Street, Medina, Ohio.

Follow Randy Oliver’s discussion of every aspect of honey bee nutrition from best diets, how, when and how much to feed, and feeding in preparation for pollination events, wintering, dearth and everything inbetween. Nutrition has become the least understood aspect of producing healthy bees. Fix that here.

Varroa. Listen and learn Varroa biology, but most importantly, Varroa control from Dennis vanEngelsdorp. Get every detail on every Varroa treatment. How, when, why, where. Varroa control chemistry needs to be perfectly understood to avoid, or reduce wax issues, and IPM Varroa controls need to be understood and used as much as, and as effectively as possible. Space is limited. Register early. Watch for details.

Next, listen in as John Miller, Andy Card and Steve Coy who are in the business of serious honey production share their secrets, their skills and even their mistakes so that they consistently make as much honey as their bees can, every year. And now so will you.

Then follow Jim Tew’s arctic, and not-so-arctic adventures in wintering. Everything from as far north as you can get to moving bees south for a kinder, gentler Winter. Refresh your Winter biology, then get better at wrapping, moving, feeding, treating and all you need to know to get bees from Fall to Spring.

SATURDAY

8-8:30 a.m. – Registration, Coffee & Pastries

8:30-12:00 p.m. – Randy Oliver, Honey

Bee Nutrition

12-1 p.m. – Lunch, provided

1-4:30 p.m. – Dennis vanEngelsdorp,

Everything Varroa

4:30-5 p.m. – Q & A, Wrap-up

SUNDAY

8-8:30 a.m. – Registration, Coffee & Pastries

8:30-10:00 p.m. – John Miller, Honey in CA & ND

10-11:30 p.m. – Andy Card, Honey NE and South

11:30-12:30 p.m. – Lunch, provided

12:30-2 p.m. – Steve Coy, Honey in SE

2:30-4:30 p.m. – Jim Tew, Winter Where You Are

Tanging

In the article,”Tanging Works Well With A Little Seed,”(Bee Culture, June 2015),the author perpetuates the tanging myth. It is well known that after issuing from their hives, most swarms settle within a few hundred yards of the hives from which they emerged whether or not one tangs. However tangers believe that if one tangs while a swarm is airborne, it will end its flight and form a swarm cluster.

This article adds a new dimension to the effect that can be achieved by tanging namely, the ability to lead an airborne swarm back to its own hive! Upon arriving at its hive, the airborne swarm then clusters on the front of the hive. A plausible alternative explanation for the beekeeper’s “success” may be that the queen of this particular colony failed to emerge with the issuing swarm and when this occurs and no other queens are present in the swarm, the swarm will return to the hive from which it emerged.

With all due respect, to assume that because several events followed one another in time they are therefore causally related is an ancient fallacy. This false premise is often expressed in Latin as Post hoc ergo propter hoc, translated as “After this, therefore because of this.”

Al Avitabile

Bethlehem, CT

Canola vs. Corn

With a protein content of 24% (vs. 15% for sunflowers, 14% for blueberries) canola pollen is one of the most nutritious of all pollens for honey bees (nutritionists recommend a minimum of 20%).

With corn prices dropping from $7/bushel a few years ago to $4 today, corn growers are looking for alternative crops but don’t have a lot of choices. Some are switching to soybeans, not the best plant for bees when pesticide programs are considered. There are about 1.6 million acres of canola in the U.S., mainly in the Dakotas, vs. 90 million acres of corn. Converting 10% of current corn acreage to canola would be a windfall for bees.

Even at current prices, corn is still a more profitable crop than canola for many growers. Perhaps a portion of the government $ targeted for pollinator habitat could be used for subsidies to canola growers (or to corn growers that convert some of their acreage to canola).

Joe Traynor

Bakersfield, CA

Beekeeping Manifesto

We often support the value of bees with economic arguments, neglecting the dimension of values, the principles we hold important and the personal and environmental standards that should be at the heart of beekeeping rather than at its fringes.

The current serious issues facing bees suggest it is time for a new manifesto to guide beekeeping, one that recognizes beekeepers as stewards of both managed and wild bees, promoters of healthy environments, managers of economically sustainable apiaries and paragons of collaboration and cooperation. It’s time for some audacious thinking about the future of beekeeping.

Such a manifesto might look something like this:

Beekeepers are Stewards of their honey bees, lightly managing colonies with minimal chemical and antibiotic input.

Beekeepers are Promoters of healthy environments in which wild and managed bees can thrive, including reduced chemical inputs and mixed cropping systems in agricultural settings and diverse unmanaged natural habitats in urban and rural areas.

Beekeeping is Economically Viable, so that hobbyists can enjoy their bees with some honey to give away, sideliners meet expenses with a bit of profit and commercial beekeepers have a consistent and sustainable income sufficient to support a family without the heavy personal stress associated with contemporary beekeeping.

Beekeeping organizations are Inclusive, Collaborative and Cooperative, encompassing hobbyists with one hive to commercial beekeepers with thousands, wild bees enthusiasts to honey bee keepers, and honey producers to pollinators, under one umbrella organization that puts the health and prosperity of bees and the environment that supports them first.

We need to recognize that the good old days are gone. Bees are no longer able to respond with the resilience that allowed us to manage honeybees intensively and depend on healthy ecosystems for wild and managed bees to thrive. Today, pesticides are ubiquitous, diseases and pests rampant, and the diversity and abundance of bee forage has plummeted.

It’s a new day, and below are just a few suggestions for what a manifesto-driven bee community might look like. Note that every idea goes against conventional wisdom, but keep in mind that these are not conventional times for bees:

Perhaps we can no longer take copious honey harvests from our bees. If so, a good first step would be to take ¼ less honey and feed that much less sugar.

Perhaps we should let colonies swarm every second year, providing a break in the brood cycle that might diminish the impact of Varroa.

Perhaps we should move honey bees no more than once for pollination, recognizing that honey bees are no longer healthy enough to sustain multiple moves.

Perhaps honey bees should no longer be considered our primary agricultural pollinator, but used to supplement wild bee populations whose diversity and abundance we increase by large-scale habitat enhancement in and around farms.

Perhaps we should allow only one Varroa treatment per year to prevent resistance.

Perhaps we should eliminate all antibiotic use, controlling bacterial diseases like American Foulbrood through a rigorous inspection and burning regime, as they do in New Zealand.

Perhaps we should cease the practice of feeding pollen supplements in the Spring, as we now understand such feeding yields higher worker populations but weaker individual bees.

Perhaps research should rigorously analyze these “perhaps” ideas. Our research community has done a fabulous job of elucidating why honeybees and wild bees are doing poorly, but what we need now are bolder research directions towards solutions.

Researchers tend towards the more glamorous high-tech solutions, but those are unlikely to succeed and at best are far down the road. Some old-fashioned, large-scale management research is needed now, coupling studies of hive survival and wild bee abundance and diversity with economic analyses of what works best for beekeepers and crop pollination.

Here’s one example: I have been travelling quite a bit lately promoting my new book “Bee Time: Lessons From the Hive,” and I consistently encounter beekeepers who are not treating for Varroa, but rather breeding from surviving untreated colonies. They report colony survival rates as good or better as those commercial beekeepers who treat heavily, but it’s all anecdotal. Let’s test those claims more rigorously, by organizing national projects to compare untreated surviving colonies to lightly or heavily chemically treated colonies.

Here’s another example: I know of no economic studies that demonstrate moving bees for pollination is economically superior to maintaining stationary apiaries, or that compare moving bees once, twice or more. My own opinion is that the extent of bee movement is a major contributing factor in the poor colony survival we see across North America, with 42% of colonies dying in 2013/2014 in the U.S. But, I know of no data that support or dismiss my hunch.

There is a changed mind-set enveloped in my brief manifesto, one in which we consider the well being of bees as the primary directive rather than economic prosperity or beekeeper convenience. Putting bees first is the only way managed and wild bees will return to health, and beekeepers and farmers with bee-pollinated crops to prosperity.

I don’t know whether this manifesto is the right direction, or the ideas above sound, but I do know that the status quo is unsustainable.

There is a quote attributed to Einstein that is highly relevant for the future of beekeeping: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

Perhaps it’s time to challenge everything we have believed about beekeeping with honeybees, and to boldly promote wild bees to become our primary commercial-level pollinators.

Perhaps it’s time to be audacious.

Mark Winston

Vancouver, BC

(Mark Winston is a former Bee Culture colunist, author of Honey Bee Biology and several bee science books, and most recently Bee Time, Lessons Of The Hive. He is Professor and Senior Fellow at Simon Fraser University’s Centre for Dialogue.

Sampling For Varroa

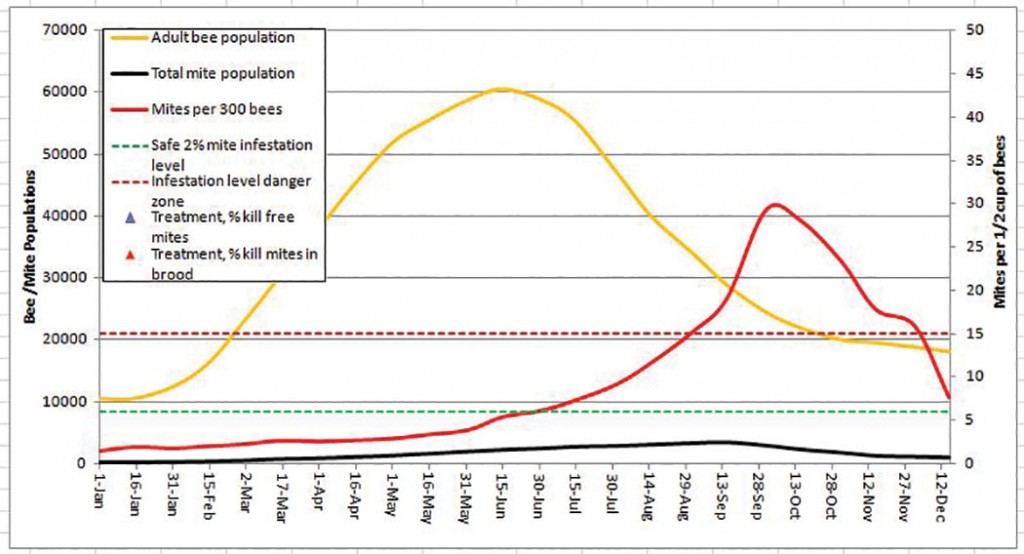

The concepts of monitoring pest population levels, and taking action as such pest levels approach seasonally-adjusted treatment thresholds is integral to integrated pest management, no matter whether we are speaking of Varroa or any other agricultural pest.

When brood is present in a hive, Varroa increase is nearly always exponential from Day 1– in non resistant bees, doubling about once a month. This is for the entire Varroa population in the hive. The illusion of linear increase in the mite population occurs for two reasons: (1) all exponential growth curves appear linear in the early stages, and (2) the bee population in a colony builds along with the mite population for the first part of the season, so the *infestation rate *(number of mites per bee) does not change to any great degree so long as the colony is also growing at the same rate as the mites.

The monitoring of the infestation rate of adult bees does not directly reflect the total mite population in the hive, since a proportion of the mites are typically hidden in the brood (about 50% for much of the broodrearing season). Natural mite fall more accurately reflects the total mite load of the colony, but needs to be considered in the context of the size of the colony, and the amount of brood emerging on that day (natural mite fall is mostly correlated with daily adult bee emergence, and typically varies greatly day to day).

The sudden increase in Varroa level in late Summer, observed when monitored by the sampling of adult bees, gives the illusion that the Varroa infestation of the colony has suddenly begun to “go exponential.” What has actually occurred is that the recruitment rate of bees tends to rapidly drop off after the main flow, due to reduced broodrearing. This results in a greater infestation rate of the remaining brood, and a shift of the mite population from out of the brood, and onto the adult bees, hence the appearance of an “exponential explosion” of the mites.

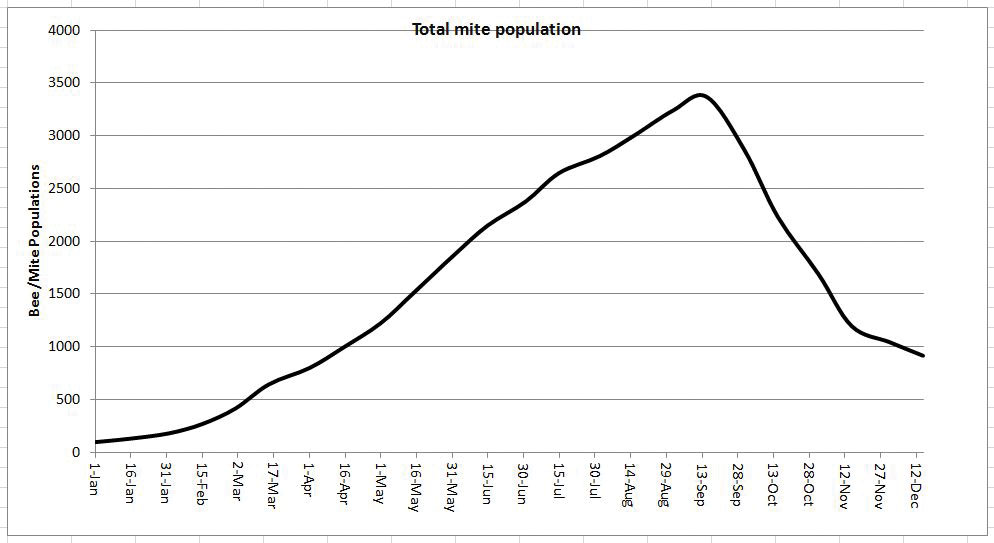

Note how the mite infestation rate “explodes” in Fall, despite the fact that the total mite population of the hive appears to have only increased relatively slightly. This illusion is due to the scale of the y axis. Allow me to plot out the exact same data for the mite population on a more illustrative scale below:

This is exactly the same mite data, but plotted on a different scale. The mite growth was exponential at first, but then limited by the reduction in broodrearing by the colony after midsummer.

The other factor that can cause a sudden increase in the mite population is immigration of mites from other collapsing hives, which typically occurs in late Summer and Fall. Robbing and drifting bees can suddenly increase the mite population of surviving hives within flight range.

The proactive beekeeper will monitor mite levels throughout the season, and apply seasonally-adjusted treatment thresholds to keep the mites at acceptable levels. It is far better for the bees to keep mite populations from building, than it is to reduce them *after* they’ve built to damaging levels.

Such seasonal treatment thresholds must take into account a number of factors, such as the point in time of seasonal colony population buildup and decline, the amount of brood present, available windows for treatment (often determined by whether honey supers are present), the method of monitoring, and the expected curve for the mite population in the near future (it declines when there is little broodrearing).

The most important concept to keep in mind is that it is not the mites that kill the colony – it is epidemics of viruses vectored and triggered by a high rate of mite infestation. So long as the infestation rate of the adult bees remains below about the 2% level (assuming complete recovery of mites by your sampling method), viruses are seldom a serious issue. As the level approaches 5%, depending upon the individual colony, in-hive epidemics of either DWV, one of the paralytic viruses, or Lake Sanai Virus begin to occur.

Such virus epidemics, as well as the rate of recruitment of new bees via broodrearing, are highly influenced by the protein intake of the colony, in the form of pollen or pollen sub.

The proactive beekeeper understands pollen, bee, and mite population dynamics, and manages his hives to prevent the *relative *population of the vector (the mite infestation rate) from exceeding the threshold at which viruses are likely to go epidemic.

Out Of State Beekeepers

Ohio State Beekeepers Association represents the over 4500 beekeepers in our state. Our purpose is to support beekeeping research, education and outreach. We are very concerned about the issues that Kim has raised regarding out of state beekeepers bringing in live bees on comb into Ohio.

The potential to expose Ohio apiaries to increased risks of diseases pests, and Africanized hybrid honey bees snowballs with bees on comb. The resulting incursion of pests and diseases, along with genetics of aggressive honey bees, will have a negative impact on the profitability of farmers, and on beekeepers in our state, now and in the future.

We support the ODA in implementing stronger enforcement of Ohio Revised Code 909.02, “for or upon moving bees into this state from outside the state, file with the director of agriculture an application for registration setting forth the exact location of his apiaries and the number of colonies of bees in each apiary, together with such other information as is required by the director, and accompanied by a registration fee of five dollars for each separate apiary owned or possessed by him at time of registration.” Along with identifying the apiary by posting the identification number in a conspicuous location and having timely inspections to identify issues before they cause problems. This information will then be passed on to county inspectors. Beekeepers in the area have the opportunity to find out if any out-of-state beekeepers have out-yards in the nearby area so they can increase pest monitoring and mitigate breeding with undesirable genetics.

We also support the Ohio Department of Agriculture in implementing 909.09, Permit necessary to transfer. It clearly states that “No person shall sell, offer for sale, give, offer to give, barter, or offer to barter any bees, honeycombs, or used beekeeping equipment without a permit from the director of agriculture.”

Tim Arheit

OSBA President