Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

Beekeeping’s Future

Despite enormous environment challenges facing the honey bee and beekeepers, there are a number of reasons to believe that the beekeeping industry is better able to withstand the uncertain future than other agricultural industries.

By: Ross Conrad

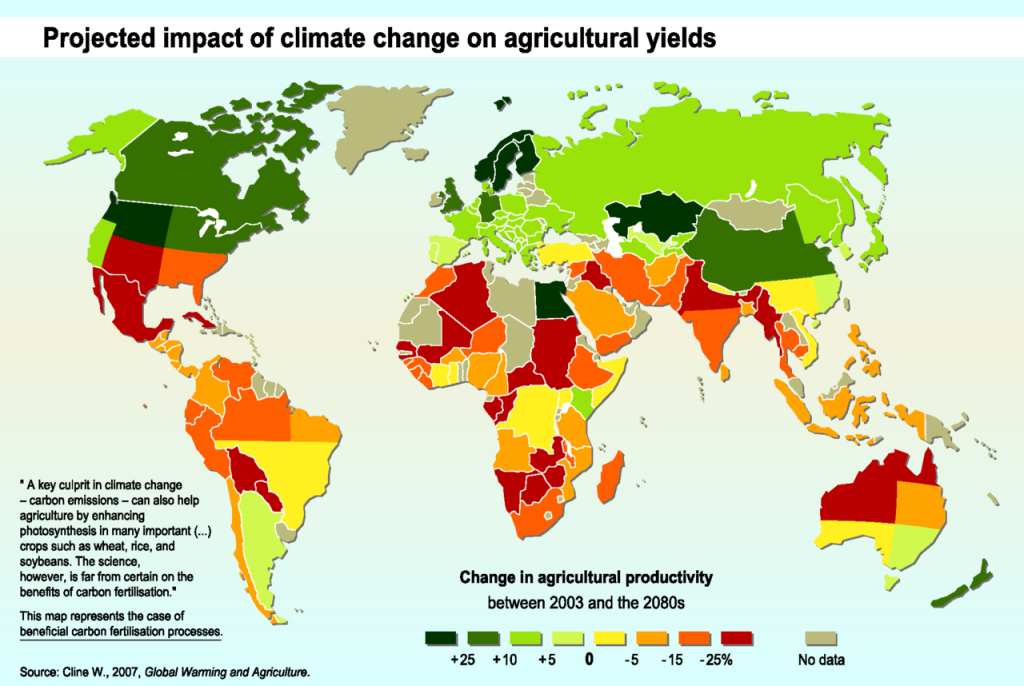

Much has been written and said about the numerous pesticide, pest and pathogen issues beekeepers are wrestling with, as it should be. What has gotten somewhat less attention is the threat that impacts all beekeepers and honey bee colonies everywhere in the world because it threatens everyone, everywhere: the climate crisis. Across the globe, climate-induced temperature extremes, droughts and floods have in some cases had a positive impact on crops. Unfortunately, the general effect of climate destabilization has been an overall reduction of crop yields (IPCC, 2022). Reduced yields lead to increases in hunger, and the resulting malnutrition related diseases, poverty and dislocated populations of climate refugees worldwide.

Climate impacts are predicted to be most severely felt throughout South, Central and much of North America. As well as Africa, Australia and parts of Asia.

Bees sip rather than gulp

To date, beekeeping and honey production has proven itself to be more resilient to climate disruption than other agricultural crops. Of course apiaries can be devastated by floods that wash away hives, or wildfires that turn colonies to ash, but bees handle drought better than other agricultural pursuits. This is because they simply require less water than most crops and livestock.

For example, farmers in Zimbabwe have found that honey production is proving to be relatively stable even while crop production in general has decreased, or in some cases totally failed (Mambondiyani, 2023). This has led to an increase in beekeeping in parts of the African continent. A side benefit from the proliferation of beekeepers is that African apiaries are helping to conserve precious vegetation in arid regions, as villagers avoid cutting trees near apiaries out of fear of the bees.

Diverse forage

One of the reasons beekeeping is proving itself to be more resilient to our changing climate is because bees often forage on wild plants and are not totally dependent on agricultural crops. This is an important trait since feral and native vegetation are often more drought tolerant than cultivated crops. Wild and indigenous plants can make up for decreased foraging opportunities when agricultural crops suffer reduced nectar and pollen production from a lack of water. The wide foraging area that honey bee colonies utilize (over three miles in every direction) helps ensure that any plants within foraging range that do have access to water and are in bloom, will be discovered by the bees.

Modest land requirements

Compared to other agricultural endeavors, beekeeping activities require the least amount of land, so farmers are often able to add honey production to their farm plan without sacrificing space for other crops. Apiaries can also utilize infertile land, or areas otherwise not suitable for other forms of agriculture.

Since beekeeping doesn’t modify or permanently alter the area in which it is carried out, it is fairly easy for an apiculturist who doesn’t own property to find land owners that are happy to provide apiary accommodations on their property. This helps make beekeeping the most accessible of all agricultural efforts, especially in third world countries and among populations with modest incomes since land ownership is not a necessary requirement to keep bees.

The pollination dividend

Through the act of pollination, honey bees increase crop quality and yields, an attribute that often causes landowners to seek out beekeepers willing to place bees on their land. Instead of being accused of stealing from neighboring farms, beekeepers receive praise for the pollination services they provide. The pollination action of bees also helps ensure the presence of wild and native species of plants and trees, which indirectly benefits wildlife as well.

Climate destabilization is making things harder for farmers, especially in arid regions like Africa.

A model of sustainability

Beekeeping is not only proving to be somewhat more resilient in the face of climate destabilization, but it can be part of the climate solution. Depending on how it is carried out, the perennial nature of beekeeping provides the potential to have one of the smallest environmental footprints in all of agriculture (Mujica et al., 2016; Moreira et al., 2019; Pignagnoli et al., 2021). The bees do most of the work. The biggest energy demands of beekeeping are in traveling to and from apiaries or migratory pollination sites. Significant energy is also required for extracting, bottling and processing of honey and beeswax. By keeping beeyards close to the honey house or farm that need pollination services, using renewable energy sources for processing, and non-plastic packaging, many of the negative climate and environmental effects of apiculture can be reduced, if not eliminated.

Since every beekeeping operation is different it can be difficult to pinpoint the exact ecological footprint of beekeeping in general. Much depends of the variety of practices such as feeding regimens, treatment practices, honey yields and shipping and transportation distances used by the beekeeping operation. Migratory beekeeping operations for example have been shown to have greater disease problems and results in bees more likely to have compromised immune systems, all of which increases the need for treatments and expensive inputs (Brosi et al., 2017; Simone-Finstrom et al., 2016; Gordon et al., 2014; Jara et al., 2021). Generally speaking, the ecological footprint of backyard beekeepers is more than three times as small as your standard commercial beekeeping operation (Kendal et al., 2011).

Unlike most agricultural activities, the very nature of the beekeeping business model provides the potential to be more sustainable. Vegetable, grain and fruit farmers typically need to buy new seed, fertilizer and agrochemicals annually, while providing tilling, irrigation and weed control. Beekeeping is a perennial activity. Beekeepers can use the same hives season after season, and as long as they are able to keep their bees alive, the need to purchase expensive inputs on a yearly basis is minimized.

It is easy to focus on all the challenges and fall into a “Woe is me” attitude considering the constant flow of bad news facing our industry. While I am not saying that things are going to be easy, there are plenty of reasons to believe that the future of beekeeping is more secure than other agricultural industries, many of which are profitable only because they are being propped up by government subsidies and taxpayer dollars. Beekeeping has the potential to provide one of the most stable and sustainable agricultural business models during the uncertain climate future that threatens to destabilize much of agriculture as it is practiced today. While beekeepings’ ecological footprint is already better than most other forms of agriculture, we can improve the current carbon footprint of the industry by finding ways to reduce emissions by minimizing transportation and shipping distances of bees, increasing the adoption of stationary beekeeping practices and by localizing, or at least regionalizing our business models.

Many beekeepers initially get involved in this ancient craft out of a concern and desire to benefit the natural world, a world that is rapidly changing and not always for the better. Thankfully, beekeeping appears to be better situated than most of agriculture to weather the unstable and uncertain future that is envisioned. Despite the numerous very real and serious threats to honey bees, there is good reason to think that beekeeping, and therefore honey bees themselves, will continue for as long as the planet’s ecosystem can support it and us.

Ross Conrad is author of Natural Beekeeping: Revised and Expanded, 2nd edition, and The Land of Milk and Honey: A history of beekeeping in Vermont.

References:

Brosi, B.J., Deleplane, K.S., Boots, M., De Roode, J.C. (2017) Ecological and evolutionary approaches to managing honey bee disease, Nature Ecology & Evolution, (1)1250-1262

Gordon, R., Schott-Bresolin, N., East, I.J. (2014) Nomadic beekeeper movements create the potential for widespread disease in the honey bee industry, Australian Veterinary Journal, 92:283-290

IPCC Sixth Assessment Report: Food, Fiber and Other Ecosystem Products

Jara, L., Ruiz, C., Martin-Hernandez, R., Munoz, I., Higes, M., Serrano, J., De la Rua, P., (2021) The effect of migratory beekeeping on the infestation rate of parasites in honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies and on their genetic variability, Microorganisms, 9(22)

Kendall, A., Yuan, J., Brodt, S.B., Kramer, K.J. (2011) Carbon Footprint of U.S. Honey Production and Packaging – Report to the National Honey Board, University of California, Davis, pp 1-23

Mambondiyani, Andrew (2023) Why farmers in Zimbabwe are shifting to bees, Yes!

Moreira, M.T., Cortes, A., Lijo, L., Noya, I., Pineiro, O., Lopez-Carracelas, L., Omil, B., Barral, M.T., Merino, A., Feijoo, G. (2019) Environmental Implications of honey production in the national parks of northwest Spain,

Mujica, M., Blanco, G., Santalla, E. (2016) Carbon footprint of honey produced in Argentina, Journal of Cleaner Production, 116(10): 50-60

Pignagnoli A, Pignedoli S, Carpana E, Costa C, Dal Prà A. (2021) Carbon Footprint of Honey in Different Beekeeping Systems. Sustainability. 13(19):11063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131911063

Simone-Finstrom, M., Li-Byarlay, H., Huang, M.H., Strand, M.K., Rueppel, O., Tarpy, D.R. (2016) Migratory management and environmental conditions affect lifespan and oxidative stress in honey bees, Scientific Reports, 6(1):32023