Click Here if you listened. We’re trying to gauge interest so only one question is required; however, there is a spot for feedback!

Read along below!

My Apiary Ecosystem

My Apiary Ecosystem

Honey bees are only a part of it.

By: James E. Tew

There’s always going to be something

In my hives or in my life, there is always going to be something – some issue or some problem. I literally just finished a phone call with one of my adult daughters. She had just eliminated a harmless Wolf Spider (Tigrosa annexa) because it frightened her young son (my nine-year old grandson). A few weeks ago, she had a problem with ants in her kitchen, but now they are gone. Now, she has Springtails (Collembola) in one of her bath showers. She complained to me that she feels that her home is under constant attack. I tried to tell her that there is always going to be something going awry. Always. Chill out. I don’t think she listened to me, but I listened to her.

Since I have spent my adult life studying honey bees, she assumed that I was also an information resource for Springtails. Readers, I don’t know anything about these small flea-sized arthropods, but unintentionally, my daughter set me to thinking and exploring. What do I know about Springtails? In all my beekeeping years, I have never asked or thought about the presence of Collembola in bee hives.

Figure 1. Springtails are about the size of a flea and seemingly cause no harm to bees or beekeeping.

Springtails are common in organic materials that are being degraded. On a whim, I keyed in a web search on Springtails (Collembola) in bee hives. I immediately got hits. All the citations that I found were from observant beekeepers. Having not found any information from academic or regulatory sources, I went to an AI open-source app and was given the following, undocumented information.

Collembola, commonly known as Springtails, are small arthropods that belong to the class Collembola. They are found in a wide range of habitats, including soil, leaf litter and decaying organic matter. While they are not typically associated with bee hives, it is possible for Springtails to be present in bee hives under certain conditions.

Springtails are detritivores, meaning they feed on decaying organic matter and microorganisms. In a bee hive, there may be small amounts of organic debris, such as pollen, beeswax and other residue, which could provide a food source for Springtails. However, the presence of Springtails in a bee hive is usually considered incidental and not a significant problem for honey bees.

I had no idea

I had no idea that these small animals could occasionally be found in hives, but my conversation with my daughter came at a time that I had been pondering this very concept. What is routinely in my bee hives and in my apiary other than honey bees? I have never found a comprehensive listing of the lifeforms that I could expect to find there.

Figure 2. Fire ants and my honey bees. Do the ants help or hurt my bees? Ants, of many species, are common in my beeyard.

My apiary is essentially a distinct ecosystem. My apiary is where I keep my bees, but I have long since realized that many other species find that an apiary is home for them, too. These “unknowns” can apparently fall into three broad categories: harmful, beneficial or neutral.

The Big List

Early in our beekeeping journeys, we are exposed to what I have named the “Big List.” Some of the common entries on this list are raccoons, skunks, ants, wax moths, small hive beetles, birds, toads and mice. It is not my intent to discuss these common hive intruders here. Yet, in the hours and hours that I have either sat by my colonies or pawed through them, I routinely see other species and wonder what they’re up to as they bum around my hives. Usually, their presence remains a mystery.

Flies

Of course, there are numerous species of flies in and around my hives and colonies. We’ve all seen them. In fact, the classic book, Honey Bee Pests, Predators, & Diseases (Morse, Roger A. & Kim Flottum. Honey Bee pests, Predators, & Diseases. A.I.Root Company, Medina, Ohio. 44691. 718 pp. Chpt 8. P 143-162.) has a designated chapter on various fly species and their effects on bee colonies. Essentially, flies and their associated larvae are degraders and generally, do not have a harmful effect on healthy bees.

Figure 3. Common Green Bottle Fly (Blow Fly), probably Lucilia sericata, parked on the front of one of my active hives.

But, I can’t help but notice the occasional Green Bottle Fly nosing around my active hives. They are very flighty and will not allow a close camera shot before taking quick flight. Why are they there? I never see them get inside the hive.

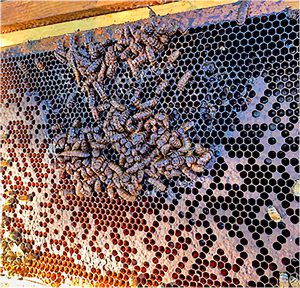

Figure 4. Black Soldier Fly larvae, H. illucens larvae, on honey bee frame. (Scott Razee photo)

But there are unique encounters between various Dipterous species and honey bees that are rare. Anthony (Auth, C. Anthony, Hauser, M. & Hopkins, B.K. A scientific note on a black soldier fly (Stratiomyidae: Hermetia illucens) infestation within a western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. Apidologie 52, 576–579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-021-00844-y) published a scientific note on a Black Soldier Fly (Stratiomyidae: Hermetia illucens) infestation within a western honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. In the article abstract, Anthony, et al. reported:

Black soldier Fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) were discovered in a weak honey bee colony in Hailey, Idaho. The larvae were localized to the brood area and caused the affected comb to putrefy. Further communication with the beekeeper revealed that the colony recently returned from California and that the larvae likely originated there as well. In California, H. illucens are common and exist sympatrically with honey bees, yet there have been very few reports of damage. We therefore believe H. illucens are unlikely to cause damage to healthy colonies or significantly impact the apiculture industry. This report is the first published observation of H. illucens in Idaho and shows conclusively for the first time that H. illucens associates with honey bee colonies in North America.

Figure 5. Adult Black Soldier Fly (Utah State University Extension)

There are distinct Diptera species that either are outright harmful to bees or other flies that are considered to be minor pests. Examples of damaging species are Phorid Flies (Zombie Flies) while a lesser pest is the bee louse (Braula caeca). These pests are documented elsewhere in the beekeeping literature. I will not cover them here.

Earwigs

Figure 6. Adult European earwigs on the inner cover of my hive.

How bad can earwigs be? In Alabama, earwigs are commonly found in honey bee colonies in significant numbers. No doubt they are found in other states. I have noted that earwigs were not a common hive resident in Ohio, but that all changed a few years ago. I now have earwigs in my office, in my home and in my bee hives.

I don’t know that they do anything within the hive. I faintly remember one Russian paper, that reported that earwigs could be alternate hosts for the bacteria causing European Foulbrood. Other than that one point, I have never heard complaints about them.

Of course, they are a pain when extracting and must be caught in the filter when processing honey. Straining bees and bee parts from honey is bad enough, but earwigs in the honey filter are unsightly. I don’t know of anything that you can do about them. In fact, I’m not sure anything should be done about them.

Roaches

As an entomologist, I respect roaches. They are the consummate survivor. Obnoxious that they are to humans, one must respect their persistence. Many, many developmental years ago, roaches “learned” to fold their wings over their bodies so they could exploit more niches, than say, a broad-winged insect like a dragonfly (dragonflies will also occasionally prey on honey bees). By storing their folded wings over their bodies, cockroaches could, more easily, get under your refrigerator or inside your bee hives. They have been a challenge for me everywhere I have kept bees.

Like so many other insect visitors/invaders, roaches are drawn to both the sweet food supply as well as the protein supplies – and then there are all the decaying larvae and adult bees to munch on. The question is begged, “Why would roaches NOT be in our hives and stored equipment?”

In the beekeeping literature, it is often written that the damage roaches do is minimal, but I want to loudly say that the appearance of just a single roach in your honey house can dissuade even the staunchest customer who is considering buying your honey. And then there is the excreta to consider. In fact, one of my most serious concerns of both cockroaches and earwigs is the excrement that they leave behind.

Figure 7. Unfortunately, a cockroach is not an uncommon hive visitor.

It is also commonly written that cockroaches are primarily found in weakened or otherwise ailing colonies. Yes, that is surely true, but I will loudly say that great numbers of roaches happily live on the inner cover of populous colonies. When the outer cover is removed, in a flash, they scamper down into the bees.

In my opinion, there is little to be done to control a roach infestation. Protecting the customer and protecting the purity of the honey product is about all that can be done. Yet, I cannot conclusively say that a modest roach infestation is absolutely harmful to the bees. Maybe future studies will continue to add information to this colony co-habitant.

Honey Bee Cousins

Figure 8. A yellowjacket lunching on one of my dead honey bees.

Yellowjackets

Though yellowjackets are on my “Big List” and are common pests in the beeyard, I have included them here. In my yards, these brightly colored insects could almost be a traditional resident of my apiary. Yellowjackets get included on my “mystery” list due to technicalities.

Yellowjackets (probably Vespula maculifrons) readily see their honey bee cousins as a potential food supply. On occasion, these wasps may have a nest in my apiary, but much more likely is that these hymenopterous insects are simply foraging within my apiary.

Experienced beekeepers have commonly seen yellowjackets mulling around the detritus at the hive entrance, but they will also enter a weakened colony and take honey, pollen, brood and adults depending on their own colony needs.

As such, yellowjackets get an entry on the common list of bee colony pests, but they do not seem to be the effective cause of the colony’s decline but are more commonly responding to a colony that has been weakened by other factors. Yellowjackets can be numerous when robbing behavior is rampant.

Figure 9. Bumblebees can frequently be seen attempting to enter a honey bee colony. This can be disastrous for the bumblebee with deadly results.

Bumblebees

I frequently see bumblebees trying to enter a bee colony. How suicidal is that? Only on a few occasions have I stumbled onto a bumble nest in unused honey bee equipment, but they are frequently in my apiary surely searching for food.

In fact, bumblebees may not necessarily be attracted to my honey bee colonies specifically, but they may be drawn to certain characteristics or resources associated with honey bee colonies. I can come up with a few reasons that may explain why bumblebees are sometimes found near my honey bee colonies:

- Floral resources: Honey bee colonies are known to forage on a wide variety of flowering plants to collect nectar and pollen. Bumblebees, like honey bees, are also generalist foragers and seek out similar floral resources.

- Odor cues: Honey bee colonies emit a combination of pheromones and odors that can be detected by other bees, including bumblebees. These chemical signals may serve as attractants, potentially drawing bumblebees to the entrance of the honey bee colony.

- Nesting opportunities: While honey bees typically nest in enclosed structures such as beehives or tree cavities, bumblebees often create nests in the ground or other protected locations. However, bumblebees may occasionally take advantage of abandoned honey bee hives or other suitable cavities near a honey bee colony, which could lead to their presence in the area.

Figure 10. The apiary ecosystem can become complicated. This mantis is eating a yellowjacket that it caught while sitting atop one of my hives.

It’s important to note that interactions between bumblebees and honey bees can vary depending on the specific circumstances and the behavior of individual bees. While they may coexist peacefully in some cases, competition for limited resources, like nectar or nesting sites, can also occur.

My core point for this article

The apiary is an active place, but not only for honey bees. Many other common and not-so-common insects and animals hang around the beeyard foraging for food or shelter. You and I take a staunch view of these unwanted visitors. But truthfully, we do not know a lot about the complex interaction between all these other species and our honey bees.

For instance, Caron (Caron, Dewey. In Honey Bee Pest, Predators, and Diseases cited elsewhere in this article.), listed more than fifteen different beetle species that could be found in beehives – usually in the bottom board litter. Most beetle species had no ill effect on our bees, but I can’t help but wonder if some of those species could be beneficial to our honey bees. Currently, no one seems to know.

In this article, I have only tinkered with a few of the species that we can see with our unaided eyes. I made no effort to review the macroscopic visitors. Examples are: protozoans, fungi and nematodes. They’re all there, too. Readers, I sense that I’m describing a bee hive supermarket or maybe a big box store for insects.

Not wanting to run amok here, but it appears to me that the apiary is a significant food and shelter resource for a lot of other insects and animals. As beekeepers, we laud the effectiveness of the workers’ defensive stinger, but this protective device does not seem to be very effective against spiders, earwigs, birds or a fungus particle. I’m guessing that out of simple necessity, bees coexist with many of these interlopers. Hive visitors come in differing sizes and represent many diverse species.

Despite everything the bees and their keepers can do, the apiary will seemingly continue to be an attractive site for non-bee species. In this article, I’m trying to ask, “From a diversified ecological position, is this necessarily a bad thing?” Consider how many other species are being subsidized and nurtured by resources from our apiaries. Could it be said that our bee hives are “community centers” for a host of non-apis species? I think so. Blame my daughter. She started this.

Thank you for reading and thinking.

Dr. James E. Tew

Emeritus Faculty, Entomology

The Ohio State University

tewbee2@gmail.com

Co-Host, Honey Bee

Co-Host, Honey Bee

Obscura Podcast

www.honeybeeobscura.com