COLOSS Beebook Volume III

Book By:

Book Review By: Kim Flottum

COLOSS BEEBOOK Volume III: Standard Methods for Apis mellifera Hive Product Research. Edited by Vincent Dietemann, Peter Neumann, Norman L. Carreck, James D. Ellis. Published by IBRA, Monmouth, UK and Northern Bee Books, Mythoimroyd, Hebden Bridge, UK. ISBN 978-1-913811-05-1. 8.25”x11.5”, 464 pgs., color and black and white, soft cover. $80 + UK postage if purchased from IBRA or Northern Bee Books (NBB) with foreign post, and the same price from Amazon (no shipping costs from Amazon).

COLOSS is a group of scientists and researchers who are standardizing how research for honey bees is being carried out. When you think about it, this makes very good sense because, simply, any scientist anywhere can now compare, essentially, apples to apples, or, perhaps more appropriately, honey bee science results to honey bee science results. COLOSS comes from Prevention of Honey Bee COlony LOSSes.

Volume 1, which came out in 2013 studies and defines standard methods for research covering such sub-categories as anatomy and dissection, behavioral studies, subspecies and ecotypes, artificial insemination, pollination and statistics. Only available from IBRA or NBB.

Volume 2 covered studies of pests and pathogens of honey bees. It standardized how surveys are conducted looking at colony losses, and then defined how diseases, small hive beetles, mites of all kinds, viruses and all the other pests and pathogens honey bees have to deal with should be examined, categorized and reported. Only available from IBRA and NBB.

Volume 3, released in October 2021, is now available. This third volume examines techniques and methods to use when studying and reporting on hive product research.

Each chapter is set up the same way. The product is described, and then produced in such a way that each time the product is identical, or not, to the last time it was produced. It is then harvested, and preserved. And then, it is taken apart and each tiny part studied, using techniques and analyses described in the book. For instance, for Royal Jelly, there are 17 pages on production, harvesting and preserving the product. Then, there are 40 some pages looking at how to do all manner of research studies on the product. It’s a long list and here are just a few….protein and sugar content, characterization of proteins and peptides, antibody purification, staining, labeling, and on and on.

The value of this information to researchers is easy to see. Everybody does it the same way, so results can be compared and measured and used by everybody. It draws these techniques from just over six pages of references. Everything about royal jelly you ever wanted to know is here. Everything. It is a scientists go-to book for certain.

The editors have reviewed all six pages of references, and have pretty much said, by including them here, this is what others have done, how they did it, and how you should now do it because now we’ll all be doing these complicated research studies the same way.

The subjects covered are done thoroughly and in depth. The first section of each product studied is basically how to produce, process, store and use each of the products. I’ve mentioned royal jelly (67 pgs), but there’s also beeswax (108 pgs), propolis (49 pgs), brood as food (28 pgs), honey (62 pgs), venom (31 pgs), and pollen (109 pgs). Figure the first third or so of each chapter is the simple collection, processing, storing and using each of these. Now that would be a beekeepers book to keep, for sure.

Each chapter has scores of charts, graphs, diagrams and such for displaying research results. And, each has good photos and drawings for collecting and preparing each, with lots of color photos and drawings. Pollen especially has excellent pollen photos for color, drawings for size comparisons and shape and more. From a beekeeper’s perspective, this is as far as I want to go when collecting pollen for my bees, or for sale. The rest of the information in the chapter is excellent for research, however, and standardization is important.

If you produce, harvest, process, store or sell any of these products, this book will pay for itself your first season. Especially if you are producing a product that needs to meet the high standards we all expect. Processing and storage is also important for consistency in sales. Seriously consider having this book on your shelf, even if you’ll only ever use half of it.

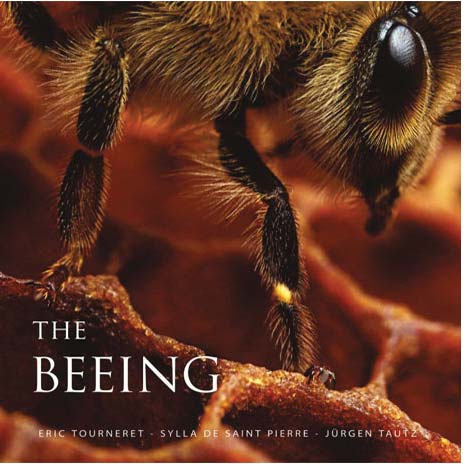

The Beeing: Life Inside a Honeybee Colony

Book By:

Book Review By: Kim Flottum

The Beeing: Life Inside a Honeybee Colony by Eric Tourneret, Sylla de Saint Pierre, and Jurgen Tautz. Published by Deep Snow Press, Ithaca, NY. ISBN 978-0-9842873-9-0. Originally published in French in 2017, translated to English October 30, 2021, by Mark Pettus, and edited by David Liedlich and Leo Sharashkin. Hard cover, 262 pages. Large format (11-3/4” x 12-1/4”), glossy color throughout. $49.95.

Eric Tourneret and Sylla de Saint Pierre are also the authors of Honey From the Earth: Beekeeping and Honey Hunting on Six Continents, published only a few years ago. To produce that first book, they spent FIFTEEN YEARS traveling the world to capture the breathtaking diversity of bees and beekeeping traditions on six continents. Epic scenes of scaling cliffs to reach honeycombs of the giant bees in Nepal… and the truckloads of hives of industrial beekeepers in America. Artisanal straw-basket hives in Romania… and the unique honeypot ants of the Australian desert. Honey traditions in the heart of the African jungle… and moving bees by boat in Argentina. Our familiar honey bees… and the most exotic stingless bees of the tropics. This is a most stunning collection of bee photography, complete with insightful commentary from a dozen leading bee experts, including Dr. Tom Seeley, Dr. Jurgen Tautz, and Kirk Webster. Shot in 23 countries.

Now, with additional input from Jurgen Tautz, Eric and Sylla have produced yet another beautiful and stunning collection of photos, accompanied with expert biology and physiology commentary for these photos. The Beeing covers all aspects of bees’ lives: physiology, colony organization, foraging strategies, nest architecture, bee intelligence, reproduction, and much more. Discover the most up-to-date knowledge on the functioning of the colony, insights into beekeeping practices, and the challenges bees face today – all written in an easy-to-understand non-technical language.

Chapters include a close look at the queen, what makes a queen and mating; the hive as a super organism and the stages of life; bees and flowers and nectar and pollen; foragers and seeing flowers the way bees see flowers; bees and humans and pesticides and breeding and honeys; nest architecture and a place to dance; bee math and propolis. Finally, Intelligence and communication looking at memory and languages and dancing and scents; and finishing with swarming and super and half sisters and genes and temperature’s assault on character.

I’ve already noted the spectacular photography, with many, many two page spreads, some showing only two bees filling both pages, with others showing a 20 acre apiary, with hives spread everywhere.

Quite simply, there is no other book like this. It’s been called the most useful coffee table book ever produced. It is actually one of the most useful books on bees ever produced.

Henry Meets a Honey Bee

Book By:

Book Review By: Kim Flottum

Henry Meets a Honey Bee. Written and illustrated by Justin Ruger. Published and distributed by Hippie Chick Apiary. ISBN 9780578995045. 30 pages, soft cover, color throughout. $15.00

Henry Meets a Honey Bee is a children’s book that uses bright colors, age appropriate art, and fictional characters to educate children on the importance and life of honey bees, one of nature’s favorite pollinators.

Come join Henry as he takes a walk, enjoying nature, and stumbles upon the adventure of a lifetime. Henry meets Honey, the queen bee of a local hive, and learns all about honey bees from an unique point of view. Watch how knowledge transforms fear to admiration for one of nature’s favorite pollinators.

I suppose if you are going to learn about bees from a bee, a Queen is about as good as it gets. And when she turns Henry into a honey bee, the learning is even better. Henry learns of pollination, visits a hive, learns of the different kinds of bees that live in that hive, the role of the queen in the hive, how workers are cleaners, nurses, builders, coolers, guards and foragers. And he even meets a beekeeper.

This is an easy to read, well designed children’s book that shows the world of bees from the bees themselves.

The Native Irish Honey Bee

Book By:

Book Review By: Thomas D. Seeley

The Native Irish Honey Bee, Apis mellifera mellifera. By the Native Irish Honey Bee Society. This book can be purchased online at: https://nihbs.org/shop/

During the last period of European glaciation, the honey bees in Europe diversified into three subspecies that survived in three refuges in southern Europe: A. m. mellifera in the Iberian peninsula, A. m. ligustica in the Apennine peninsula, and A. m. carnica in the Balkan peninsula. When this period of glaciation ended, about 12,000 years ago, the subspecies A. m. mellifera expanded its range far to the north. Its colonies spread to northwest Europe (the British Isles and Scandinavia), to north central Europe (north of the Alps), and even to north central parts of Asia. They also adapted to each of these regions. This produced the Irish black bee, the Dutch black bee, the Alps black, the Nordic black bee, the Welsh black bee, and still more. Each of these forms of A. m. mellifera is an ecotype, i.e., a population of honey bees which possess genetically-based traits that contribute to their ability to survive and reproduce in their particular location. Broadly speaking, the workers of A. m. mellifera differ from those of A. m. ligustica (Italian bees) and A. m. carnica (Carniolan bees), in being larger bodied, longer haired, more capable of flying at low temperatures (5°C/41°F), more avid collectors of propolis, and better able to survive long winters as small colonies that are frugal with their honey stores.

These days, the largest population of A. m. mellifera is found in Ireland, and the book The Native Irish Honey Bee provides us with a marvelous synthesis of recent work on the biology and the keeping of this bee. It is also a remarkable book in that it was written and produced entirely by members of the Native Irish Honey Bee Society (NIHBS). Some are biologists, some are beekeepers, and many are both. All have love for and pride in their native honey bees, and all have shared their knowledge in the cause of conserving these bees. The Irish, by the way, have a long tradition of writing about their bees. The oldest Irish legal manuscript dates to before 1350 AD, and is called Bechbretha (Bee Judgments). It covers legal decisions dating back to 700 AD regarding such matters as the rights of the neighbors of a beekeeper to receive a share of the honey crop because his/her bees trespass on their properties. Evidently, this was a sticky matter, and it needed a legal resolution.

The book’s chapters are grouped into five sections. The first—The Native Irish Honey Bee—delves into the basic question of defining the native Irish honey bee. It is argued, quite cogently, that it is a genetically distinct population of A. m. mellifera that is adapted to living in the mild, but damp, oceanic climate of Ireland. It is not known whether this bee was introduced by Celtic-speaking people who came to Ireland in prehistoric times, or it reached Ireland even earlier, when sea levels were lower and present-day Ireland and England were part of the European mainland. One thing that is known is that the native Irish honey bee is the largest and most important surviving population of A. m. mellifera. One chapter in this first section describes the genetic analysis of 412 bees sampled from 80 sites across 24 counties (of 32 total) in Ireland, and it reports that 97.8% of the sampled bees were found to be pure A. m. mellifera. Evidently, the rate of importation of queens of non-native subspecies (e.g., Italians and Carniolans) has been low, or the colonies headed by native queens have survived and reproduced better than those headed by imported queens, or both. This genetic analysis also revealed numerous unique alleles of the bees’ mitochondrial genes. This discovery tells us the Irish population of honey bees has evolved independently since the closure of Ireland’s land bridge with Britain, thousands of years ago.

The book’s second section—Conservation— examines strategies for the conservation of A. m. mellifera in Ireland. The first chapter explains that this is a thorny matter, because the legal status of honey bees in Ireland is somewhere between that of domesticated animals and wildlife; neither status is quite right for honey bees. One conservation approach being used already to support the native Irish honey bee is to establish voluntary conservation areas reserved for these bees. For example, members of the Galtee Bee Breeding Group are keeping and breeding only native honey bees in the Galtee and Vee Valley areas. Subsequent chapters include one by Micheál C. Mac Giolla Coda, titled “Rewilding the Irish Honey Bee” in which he describes how beekeeping was in the past, and how already there is evidence from a “Free-Living Bee Survey” that there are colonies surviving on their own. The chapter “Wild Apis mellifera mellifera in Ireland”, by Professor Grace McCormack, discusses an on-going study of the genetics of wild colonies in Ireland, and reports that the workers sampled from these colonies have a probability of 0.99 of coming from a lineage of A. m mellifera queens. This is a clear sign that, in Ireland, the native Irish honey bees have greater fitness than those from elsewhere in Europe. This section of the book ends with a thoughtful chapter “Bees and the Environment, by Willie O’Byrne. He discusses changes in the farming and the floral landscape in Ireland, and offers many suggestions for farming, urban beekeeping, afforestation, and hedgerow management that will improve the lives of both honey bees and wild (non-Apis) bees.

The third section focuses on queen rearing. It includes six chapters that show how easy it is to improve your bees for winter hardiness, disease resistance, and honey production. The first two chapters, by Aoife Nic Giolla Coda and Jonathan Getty cover the biology of queens and drones, and the logistics of setting up a queen-rearing group. Next comes Michael Maunsell’s chapter on how to improve your bees. Front and center, he makes the point of “Take the bees that are native to your own area and work with these.” Even in Ireland, a relatively small island, there are great differences in climate and vegetation, and beekeepers there want bees that are suited to where they live. Maunsell notes, too, that colonies that are heavier propolisers “are generally healthier or better able to handle disease.” The next six chapters, by Tom Prendergast, Colm ÓNéill, Jane Sellers (three), and Irene Power, describe each author’s tools and methods for rearing queens and getting them properly mated. Some are traditional (collecting swarm cells and using 5-frame mating nucs) and others are modern (Jenter kits and Apidea mating nucs). All have been tested by the authors’ experiences in Ireland over several decades.

The fourth section— Four Corners— is very special, for it comprises personal accounts of some of the Irish beekeepers who have long championed the native Irish honey bee. For example, Gerry Coyne, of Connemara on the west coast, describes beautifully his early years in the 1960s of working with the native bees—”kind creatures that were docile and content carrying out their work”—using no veils, or just ones improvised from lace curtains. Likewise, John Summerville, a beekeeper with 40 years of experience in Galway, writes “we need to protect and nurture our own black native bee as she serves us well with her calm nature and ability to forage in typical Irish weather.” There is also the inspiring piece by Michéal Mac Giolla Coda that describes the origins of the Galtee Bee Breeding Group. He also explains how the protection (from non Amm drones) of the group’s mating apiary was inspired by the prehistoric fortress on Inis Mór, one of the Aran Islands off Ireland’s west coast. These three contributions, plus the others found in this section, show much that is special about the beekeepers, as well as the bees, in Ireland.

The fifth section—The Past, The Present & The Future—contains five chapters. The first, by Jim Ryan, does a fine job of reviewing the history of beekeeping in Ireland over the past 1300 years with emphasis on the period from the 1850s (following the Great Famine) to the present. Photos of beekeepers and their hives, from the 1880s to the 1920s are a special treat. The second chapter, by Eoghan Mac Giolla Coda, provides a clear and precise description of what it is like to be a commercial beekeeper in Ireland. I found his tables on such things as the monthly mean maximum temperature, the monthly mean rainfall, and his annual honey production per hive very helpful in getting a clear picture of the conditions of beekeeping in Ireland. Beekeepers will also appreciate his careful descriptions of the hives he uses, and of how he deals with the challenges of swarming, propolisation, and disease susceptibility. The third chapter, by Redmond Williams, “Preparing for the Season Ahead,” is well named, for he describes his system for doing just this. He cites the old saying “There is no point in sharpening your sword when the drum beats for battle.” The fourth chapter, by Tanguy de Toulgoët, provides a ten-point (“Ten Commandments”) program for managing colonies in Warré hives to help increase the population of wild colonies of Apis mellifera mellifera in Ireland. I like his program, and hope that it will be followed by those who are interested more in being a bee watcher (akin to a bird watcher) than in being a beekeeper. The closing chapter, by Mary Montaut, poses two questions about the future of bees: “Can our beloved bees outlast the harm which human activity is undoubtedly doing to the earth? And if so, how can beekeepers help them?” I have asked myself these two questions, and I hope that bee biologists, beekeepers, and other concerned people will muster the collective intelligence that we will need to answer these questions with “Yes!” and “Here’s how.” After reading this book, I am confident that the natural “laboratory” of Ireland, and its resilient native Irish honey bee, will play an important role in helping us find ways to protect the future of bees.

Common Sense Natural Beekeeping

Book By:

Book Review By: Dewey Caron

Common Sense Natural Beekeeping Paperback, 128 pages • $24.99 US, $32.99 CAN • ISBN: 9781631599552 • Quarry Books. You can preview the book here: https://bit.ly/3yFh0A2

The newest book by Kim Flottum, Common Sense Natural Beekeeping, co-authored with Stéphanie Bruneau, needed to be written. It very succinctly covers sustainable beekeeping using “limited chemical or human intervention.” It will be perfect for individuals who wish to Save the bees but not treat nor manage their bee colonies like conventional livestock.

New beekeepers quickly learn, and established beekeepers are well aware, that honey bees face numerous stressors. Wide adoption of chemical treatments as necessary for varroa mite control have become standard. Rather than spending our time continually at war with varroa mites, using a “battery of chemical treatments” Common Sense Natural Beekeeping covers the “middle ground between micromanagement and no management…. it allows the bees, the environment and the beekeeper to thrive.” in the words of the authors.

The authors believe we should approach yearly colony losses differently and adopt “an acceptable alternative.” Contending that natural colonies are “thriving” without our intervention, we need to learn how better to manage our backyard bees. Their approach is to return to a more natural handling and housing of bees. We need to first learn then to partner and participate in colony care rather than seek to dominate our bees. It is a stewardship of cooperation from respect, not from control.

The book is extremely well illustrated – 35 pages are photos alone. The cover is outstanding and really captures the essence of the book. Amber Day is credited with its design. There are two pages of background reading and research and a useful index. The last section includes final recommendations “Bee like a Bee would Bee” – a neat summary of the Common Sense philosophy of the book.

The first pages describe the authors philosophy of bee care. It provides back ground on the life of bees in the wild. The work of Dr. Tom Seeley, who has extensively researched bees in bee trees, is summarized. His studies form the framework that “helps us make modifications to create healthier and more habitable hive systems.”

There are three sections of information. For the first section Home Sweet Home, different bee hive designs are covered. Chapter 2, over one-third of text, describes and lists pros and cons of eight different hive designs. Real-life practitioners are included of adapters for each hive. For the Langstroth hive, cons (9) outnumber the pros (2) but eight “adaptations” are listed for how individuals might “improve the bee approval rating.” The pros outnumber cons for Warré, Top Bar, Layens and skep (modified as a sun) hives. Log hives, the Custos and Eco Tree hive are also discussed. There is a companion chapter on Hive siting entitled “Real estate decisions.”

A second section discusses three major bee stressors – bee mites, swarming and “what’s for lunch” (bee nutrition). Natural beekeeping for varroa management includes stock selection, best hive, proper nutrition and more intensive management. Each of these is light on text, more of the philosophy compared to practice. Swarming coverage includes prevention and control. Keeping bees in smaller hives and swarming is described as “natural selection to create strong and healthy colonies [that] decrease the hive’s problems with varroa mites.” The final chapter discusses the importance of a varied diet for proper bee health.

A third section includes a two page case study discussion of five individuals that are using Common Sense Natural Beekeeping. It nicely illustrates how the philosophy of gentler, sustainable beekeeping might be achieved via use of a different hive and chemical-free management of honey bees. These help illustrate how by observing the way bees live in the wild, beekeepers learn to make management decisions including hive design that incorporate the bees innate intelligence and behavior for sustainable alternatives for natural hive management.