By: Anne Marie Fauvel & Nathalie Steihauer

Bee stories abound and are as colorful as some of the keepers that tell them. Differences in operation sizes, circumstances, philosophies and opinions are what makes this group so interesting. So, who are the beekeepers and what role do they play in honey bee colony health? At the Bee Informed Partnership, we use data to tell bee stories.

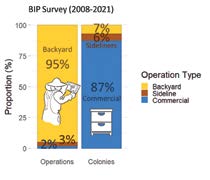

Figure 1 Proportion of beekeepers of each type of operation (left) compared to the cumulative number of colonies managed by each size of operation (right).

In the BIP National Colony Loss & Management survey, we group beekeepers by operation type, based on the number of colonies they manage. We define backyard beekeepers as those keeping 50 or fewer colonies, those keeping between 51 and 500 colonies are classified as sideliner beekeepers and those managing 501 or more colonies are considered commercial beekeepers.

According to the last 14 years of the BIP survey data, backyard beekeepers represent the vast majority of beekeepers (95%) but account for only 7% of colonies managed (Figure 1). Conversely, commercial beekeepers represent only 2% of the operations, but manage most of the colonies represented in the survey (87%). We have good evidence to show that this ratio is a fair representation of the US beekeepers thanks to the NASS Census of Agriculture, despite the fact that only operations that qualify as “farms” are counted in the Census. According to NASS Census, operation types rank at 93%, 4% and 3%, and colonies number at 6%, 9% and 85% for backyard, sideliner and commercial beekeepers respectively (special tabulation provided upon request by NASS).

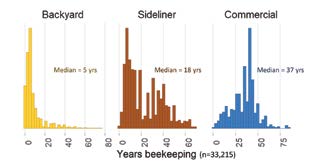

Figure 2 Years of beekeeping experience for backyard beekeepers (yellow bars on the left), sideliner beekeepers (red bars in the center) and commercial beekeepers (blue bars on the right).

Back to the BIP survey results, in the U.S., backyard beekeepers have a median of three colonies, sideliners have a median of 100 colonies and commercial beekeepers have a median of 2,000 colonies, with some of the larger operations tallying 50,000 colonies or more. Interestingly, the level of beekeeping experience for each group varies significantly. Figure 2 shows an average of five years of beekeeping experience among backyard beekeepers compared to 18 years for sideliners and a whopping 37 years of experience for commercial beekeepers.

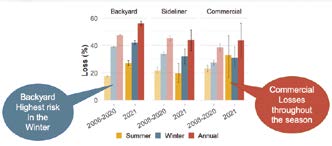

Figure 3

Average historical colony loss percentages for summer (yellow), winter (blue) and annual (red) for 2008-2020 (light colored bars) compared to 2020-2021 beekeeping season (brightly colored bars) for backyard beekeeper (zero to 50 colonies), sideliner (51-500 colonies), commercial (501+ colonies).

Separating the responses by operation size also provides an interesting look at seasonal and annual losses. Figure 3 shows that over the full 12-month season (red), backyard beekeepers experience greater annual losses than commercial beekeepers. A potential explanation for the lower annual losses by commercial beekeepers can be seen by looking at the Varroa management practices across operation sizes shown in Figure 4.

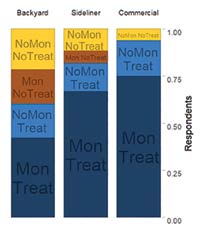

Figure 4 Proportion of respondents for each type of operations, backyard (left), sideliner (center) and commercial (right) beekeepers who do not monitor & do not treat (yellow), do monitor & do not treat (red), do not monitor & amp; do treat (light blue) and do monitor & do treat (dark blue).

Nearly all (>95%) commercial beekeepers treat for Varroa and over 75% both monitor and treat for Varroa. These practices are less prevalent among backyard beekeepers with about 60% reporting that they treat for Varroa and less than 50% performed both recommended practices (monitoring & treating).

In addition to higher annual losses, backyard beekeepers tend to have a higher proportion of losses occurring in the Winter (October through March) than in the Summer (April through September), which contrasts with commercial beekeepers who tend to lose their colonies more equally between the two seasons.

This might result from commercial beekeepers being more likely to abide by the old adage “take your losses in the fall” and combine weak colonies before the Winter. For commercial beekeepers, it is often not worth the time, energy, or resources necessary to attempt saving weak or small colonies when they can combine colonies to have a better chance of being viable pollination units in the spring. So, keeping in mind the different types of beekeepers, their level of experience and how this all translates into Varroa monitoring and treating practices and colony losses, what type of beekeeper are you?