How hard can it be?

Well, it’s complicated.

Try this. Go to the established bee book of your choice and look up supplemental feeding. Be prepared for some extensive reading. Since I’m writing for Bee Culture magazine, I went to ABC and XYZ of Bee Culture. The supplemental feeding section in the new text is exhaustive – as it would be in most beekeeping textbooks. As is always the case in all-things beekeeping – if you have a lot of options – then the absolute best way for performing the task at hand has not been fully chosen. Supplemental feeding of bee colonies certainly fits that bill. There are presently many proven ways to feed bee colonies.

But it’s not natural

Supplemental bee feeding is little more than beekeeper-assisted robbing. I suggest that foragers taking sugar syrup from a feeder have little in common with that same forager imbibing nectar from an apple blossom. “But Jim, feeding procedures are in every bee book.” All beekeepers do it. Bees obviously love it. All those comments are true and feeding serves a good management purpose, but it’s a beekeeper-developed task and is not practiced by bees in nature. I sense that is why there are so many varied techniques for supplementally feeding needy bee colonies. There is no best way to feed bee colonies.

(Crudely) Estimating colony strength

First, does a colony even need feeding? “Hefting” the colony is a common but easy way to check your colonies relative food stores. If you tip your colony forward, and it feels as though it is nailed down, it probably has good supplies of honey stores. It should be dead heavy. If the colony tips easily, even if it is sitting on a firm hive stand, the colony will surely need extra food stores. At this point, the “north beekeeping vs. southern beekeeping” issue becomes important. Bees can generally be fed during most cool months in the southern and southwestern U.S., but not so much in colder climates.

Figure 1 Sometimes, bad luck just happens. Years ago, a late season Winter squall made it difficult for bees to use my syrup feeders. Happily, most survived.

In more northern locations, bees will be clustered much more during the cold season so they will not be able to leave the cluster to visit a Winter feeder. Feeding wintering bee colonies – anywhere – is a last-ditch desperation procedure. In warm areas, the feed must be continuously present. In colder climates, the bees can’t consume the feed on many days. Going into Winter with colonies light in stores is never the best management procedure but all nectar flows are not necessarily great flows. Even for the best beekeepers, sometimes late season colonies are lightweight. That’s when beekeepers can help.

Supplement bee food options

Honey in the comb

Honey in the comb is the best emergency food for hungry colonies. Obviously, few of us have significant amounts of reserved honey in the comb. But if perchance, it is available and disrupting the colony as little as possible, place full honey frames near the cluster. Ideally, the day should be warm so the bees could move to the honey. If the day is cold, be sure not to break the cluster.

Liquid honey

At first consideration, it usually makes very little sense to extract honey and then feed it back to the bees, but there are occasional instances. In my personal experience, the following event has happened to me several times. I acquired full deep-frames of honey from Winter-killed colonies. In truth, the colonies were Winter mite-killed colonies, but regardless, I had honey remaining in combs. I wanted the old honey removed from the combs so I could reuse them; therefore, I did all the extracting work and acquired honey that I did not want to use for human consumption. So, I acquired several buckets of usable but not high-quality honey (by my standards).

Figure 2 An old photo of a homemade top

feeder used to feed diluted honey back to bees.

Why not just sell it for animal feed use? Why not use it in cooking? Why not strain and filter it, then blend it with better honey? Yes, all these suggestions are viable options, but in theory, I am only selling this substandard honey to acquire money that I will then use to buy granulated sugar.

(I hope I don’t get a lot of unhappy mail for the brief discussion that follows.) Much like the comment I make in the following section on corn syrup, a full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this general article, but a few comments seem appropriate.

Anytime re-feeding honey is discussed, there is always a stern warning attached that American foulbrood or other viral infections could be transmitted when feeding honey from unknown sources. While I have read that warning hundreds of times, I cannot cite a single instance where it was conclusively documented to have happened. Not a single one. But, yes, technically, it could happen.

In my case, I know the honey source and foulbrood was not the issue that killed the colonies. General recommendations suggest that the honey be cut about 30% with hot water, mixed and fed back to the bees in quantities that the colony can consume overnight. My bees loved it.

Having written all of this, honey stores refed from Winter-killed colonies is not a good way to accumulate feed for hungry bees. But new packages will surely appreciate the food boost.

Corn syrup

Corn syrup is a common carbohydrate supplemental feed for bees. It requires no mixing and seemingly is a nutritious honey substitute and is available from bee supply sources. However, some formulations of corn syrup have become suspect when used as Winter food sources. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is frequently fed to bees but concerned discussion has been directed toward that artificial feed. Some of you like it, some of you don’t1. Maybe in future articles, we can more fully discuss this concern.

Sugar syrup

For beekeepers with a small number of colonies, feeding common table sugar is the traditional bee feed. For Winter feed, mix two parts granulated sugar to one part water by either weight or by volume. Heating the mixture will help it go into a more concentrated solution. The exact ratio of sugar to water is not particularly critical. But always remember that it is the sugar – not the water – that the bees need as a food source. If you scrimp – scrimp on water and not sugar.

Granulated sugar can be fed dry. It is simply mounded around the inner cover hand hole – most likely poured on a sheet of newspaper. Bees move up, gather the sugar, mix it with water, and use it as an immediate food source. If bees can’t fly to water, they can (apparently) use a small amount of metabolic water produced by bees in the hive, but in general, if feeding dry sugar, bees should have ready access to water.

Figure 3 Bees feeding on granulated sugar that was poured on the inner cover.

Fondant

Earlier in my beekeeping youth, in the beekeeping literature, there were common procedures for making candy boards or for making fondant to feed bees. Such procedures, as I recall, required cooking the mixture, mixing cream of tartar and possibly some vinegar. It was a significant task. I don’t recall ever doing it a single time. It was just too easy to feed sugar syrup.

Always searching for easier ways, in later years, I approached a commercial bakery supply. Not knowing what product for which I was searching, I asked the baker for a sugar paste much like that found in the center of Oreo® cookies. I clearly recall the supplier saying, “Oh, you want something like Karps2 bakery fondant.” I bought a box of it. The bees seemed fine with it. In later years, this specific product name was changed, but I have still been able to purchase commercial fondant. You will need to find your own local source. In a few somewhat rare instances, feeding solidified sugar paste could be a useful procedure.

What common feeder device to use?

All feeders are positioned either inside the hive or outside the hive. There are numerous designs of feeders, but none are perfect. Most of these devices have about as many advantages as disadvantages. You decide.

Bulk feeders

Figure 4 An Assortment of Feeders

Bulk feeders can be used to open-feed bees. So far as I know, no bulk feeders are commercially available. Many years ago, I cut a 55-gallon drum in half, the long way and improvised two large troughs. Using wheat straw as floats, I quickly fed large amounts of sugar to the colonies in my yard – and to countless other neighborhood colonies that also found the source.

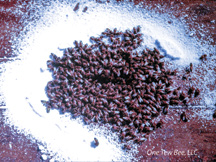

Sugar feed, usually syrup, is simply put in open containers in the bee yard for the bees to gather themselves. The weather must be warm and flight conditions must be good. While easy to implement, this procedure encourages robbing and fighting among the foraging bees. There is also a risk of disease and pest spread. And finally, you are feeding all the bees in the community – not just yours – when using this system. While the procedure worked for me and was simple, I did not use the system very often.

I know commercial beekeepers who have used this procedure, but it is not the best methods for those of us – like me – who are keeping smaller numbers of colonies in urban apiaries.

Figure 5 Foragers taking feed from an open source. I cannot recommend this procedure.

The classic Boardman Feeder

All beekeepers seem to have one of these gadgets. They are a right-of-passage device for beginning beekeepers. It is used at the hive entrance, and is the most convenient, but least effective of the hive feeders; however, this simple feeder is a good device for new beekeepers to use. The drawback is that wintering bees must walk too far to gather the syrup. Another disadvantage is that leaking Boardman feeders entice robbers to the entrance of the needy colony. You can easily use these devices but be forewarned.

The typical division board feeder

The division board feeder is an internal feeder that gets food nearer to the cluster but often too many bees drown in the feeder; plus, the bees must have warm weather to make the trip to the feeder. The division board feeder can be located essentially anywhere in the hive, but generally the feeder is put at the wall of the hive, where it can be easily filled.

Hive top feeders

Beekeepers, in many ways, this is the best device to use. It has a fairly large capacity and is easily filled. It is readily available to inside bees, and if used during cool months, it is close to the cluster. Several designs are available from commercial supply companies or top feeders can be made in the shop.

I have found that an empty hive top feeder can be a place where burr combs are put for bees to clean them. Also, these empty feeders can be used for storing things like empty queen cages, matches or your hive tool.

A quirk of leaving the empty hive top feeder on the hive is that the bee restricting mechanism should be removed to allow the bees into the feeder basin to chase away ants, earwigs, roaches, or small hive beetles that would otherwise occupy the empty top feeder.

Figure 6 An old photo of a classic Boardman feeder.

A unique variation of the hive top feeder, that I like, is a unit that puts the feeder on top of the outer cover. The bees take the syrup from the feeder through a hole in the outer cover. The plastic feeder attaches to the outer cover with an attachment device where it can be easily viewed and removed for filling without disturbing the bees.

Chicken or bird watering devices

Variations on chicken or quail watering devices can be used to feed bees. While the typical device holds approximately two quarts, and bees readily use it, I have found that forager bees get inside the device as it empties. Dumping the bees from the container agitates them.

Comb filling procedures

Using a new hand compression sprayer commonly used for applying pesticides, sugar syrup can be sprayed into open combs. When sugar-syrup-filled combs are put back into the hungry colony, the syrup is quickly gathered, concentrated, and reprocessed into food stores or is immediately consumed.

Figure 7 A telescoping hive top with attached feeder.

This is one sticky, messy task, but the supplemental feed in combs can be put near the bees. Any syrup not quickly consumed will crystallize, but the bees can still use some of the sugar crystals. Like several other feeding methods, this procedure works, but I rarely use it now. I have too many other options available to me.

For many years, a major bee supply company manufactured a gasoline-powered comb filler, but the device can now only be found as a secondhand device or at bee equipment auctions. Yes, it too was messy and expensive, but it worked.

Some final thoughts and comments

Mold

Many feeder containers will begin to support mold growth after a few uses. While this mold is (apparently) not harmful to the bees, it will plug feeder holes and is unsightly. It is annoying to clean but is a common side effect of feeding carbohydrates to bees.

Controlling the syrup flow rate

Whatever container you decide to use must have a firmly seated lid. Essentially, the upturned jar/container forms a vacuum that allows the syrup to drip or to flow very slowly. If feeder holes are too large (the diameter of a common frame nail seems about right) or the lid is not firmly seated, syrup will drain out too fast and flow out the front of the hive or drip through the screen bottom board. Robbing becomes a problem.

Allowing the bees to propolize the feeder holes closed

After the bees have emptied the feeder container, I leave it on the colony. Within just a few days, the bees will propolize the holes closed. The next time I use the feeder, I only open enough of the holes to allow syrup to flow at a controlled rate. If I want to provide a heavy flow from the container, I will punch more holes open.

It’s not a perfect procedure

Spring feeding is normally practiced for stimulation and brood production. It’s easier than Winter feeding. Feeding bees for survival is always a desperation procedure. At best, colonies will be kept alive but don’t expect them to thrive. If possible, when preparing colonies for Winter, leave abundant honey stores on the hive for the colony to use. All too often, beekeepers spend time, energy and money on desperate Winter bee feeding procedures only to have the colony die anyway. It is far better to go into Winter with the colony prepared than to attempt long-term feeding – no matter what your climatic conditions are.

Feeding protein

I am out of article space here but feeding protein should be acknowledged in this piece. Pollen supplements are commercially available and are significantly helpful. But feeding protein is not like feeding carbohydrates. This process needs its own discussion at another time. Protein feeding is just one more task for the worried beekeeper.

Thank you

As usual, if you are reading this “thank you,” you are a persistent beekeeper. I appreciate your time and any comments you might have on your experiences. Thank you for reading.