By: John Gordon Sennett

Photo 1

Photo 2

June 26, 2023 was a quiet cool day in Kyiv, Ukraine. No Air Raid sirens woke us in the middle of the night. Just two nights before, missile debris had struck a building killing four people in the Solom’yanskyi District. The very district we used to live in and would have to travel through for our first ever visit to the Ukraine National Beekeeping Museum (Photo 1). My wife’s (Natasha) maiden name is Prokopovych on her Ukrainian side. Petro Prokopovych (1775-1850) is widely recognized as the first ever designer of commercial beehives with his movable frame hive (see Photo 2). Natasha was excited even though the Soviets had destroyed most birth records and she has no idea if she is a direct relation of this famous Ukrainian beekeeper. I was excited because I had wanted to visit ever since we moved to Ukraine in November 2020 and then the war stopped all essence of normal living. We have merely learned to live with the war and today’s outing was highly anticipated. Plus, we would be meeting our friends who are considering their own apiary in the south of Kyiv Oblast.

Photo A

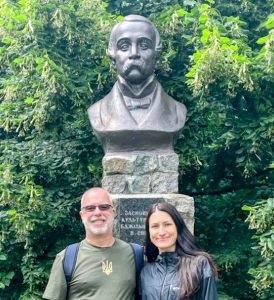

Our Uber driver professionally wove through traffic and soon enough we arrived at the gates. A worn sign identified the grounds of the museum as the “Prokopovych Institute of Beekeeping” (Photo A). Our friends were running behind and as we entered the gate, the guard informed us the museum was closed. My wife rattled off her fluent Russian and soon enough, a phone call was made, the gates opened. Once you step inside the gates, the urban environment completely disappears. We first encountered a single apitherapy house along with wood-carved gnomes the size of small logs. Meandering down the lane, an older woman was pulling weeds near the statue of Petro Prokopovych. Natasha spoke with her briefly and we continued on. Soon, we came upon all different styles of beehives from the old log hives to Ukrainian-style long hives to some Slovenian and others. All this on display in the outdoors. More whimsical log gnomes greeted us along the way (Photo 3).

Photo 3

Soon enough, we encountered a man who greeted us and asked us our business. We informed him we wanted to see the museum. He had to check higher up the ladder and told us to wander a bit while he did so. Further down the lane, we came across an Orthodox Christian chapel with various saints who were known as beekeepers. The inside was closed but the exterior was well adorned. We continued on, our friends informed us they were running late and stuck in Kyiv traffic. At the end of the lane, we came across several active Langstroth hives in a small beeyard. I could tell that two of the hives were strong but a third was weak based on the activity in and out of the hives. Soon enough, our guide was inquiring if our friends were coming and he was beginning to look impatient. A few moments later, we saw them making their way down the lane.

Our guide never gave us his name or maybe I missed it when he did. Once we were all together, he became very enthusiastic. Since my wife is a Russian speaker, he chose that language instead of Ukrainian. Our friends are also fluent in both languages and I get by a little in both. The first room we enter holds old farming instruments from the 1800’s along with a loom to show the tradition of Cossack self-sufficiency. Petro Prokopovych came from a family of priests of Cossack origin. Various implements for shearing sheep and combing the wool lie around, an old horn instrument and several garments with the signature embroidery style of Ukraine.

Next, we enter a full room of preserved hives and other beekeeping instruments. Here, there is a perfectly preserved Prokopovych Hive (See Photo 2). There are old Slavic log hives on one side of the room. Ukrainian-style long hives in various forms, some painted with elaborate Cossack scenes and other hives from Poland, the Baltics and Slovakia line the walls. Our guide shows us queen nucs with wax still in the frames. Also, a very interesting box that I thought was a nuc box turned out to be an apitherapy box that a healer carried with them when using bee stings. A large painting of monks tending beehives adorns one wall of the whole room as well. We probably could have stayed there another hour but being the museum wasn’t “officially” open, we didn’t want to press our luck.

Our guide politely showed us into the next room where there sat a model of “The Swallow’s Nest” which is a famous castle on the coast of Crimea, now occupied by the Russians. The most amazing thing is that our guide opened it to reveal that it was once a decorative, functioning beehive with customized movable frames.

Just off that room, stood one of the great treasures of the whole museum. A room full of products made from beekeeping. There were two whole cabinets of apothecary items from a century ago to modern times. An apitherapy inhaler sat lonely next to them. A full cabinet of various beekeeping tools from wax scrapers, framing implements, hive tools and other sundry items known to most beekeepers stood to the left. Three cabinets with various items made from beeswax from the practical to the artistic kept us all mesmerized for quite a while. There was even a copy of Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” cast entirely of beeswax. My friend Kostya and I were intrigued most by the last cabinet. It contained a complete collection of various alcoholic spirits made from not only honey but propolis and a bottle of sake said to be made from the remains of dead bees. We didn’t want to leave this room and there was hardly enough time to examine every single item.

Photo 4

Our guide got very excited as he led us into the last room. The electricity flickered on and off as it often does in the war. He was downcast and we all stood there for a minute discussing some of the displays we had seen. A whir in the background and the lights came on and our guide smiled as he lit a full diorama of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra (Photo 4). This monastery is the most famous in Kyiv because it is the foundation of Orthodox Christianity in most of the Northern Slavic lands founded in 1051. In 2013, the International Beekeeping Congress (Apimondia) was held in Kyiv and a tour of the monastery’s apiary was part of the program. Orthodox monks produce honey, beeswax candles and other products to this day. Now, during the war, the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra is another battleground for Moscow’s control of Ukraine. Yet, the monastic beekeepers, we assume, still look after the apiary.

Just as we were about to wrap up our tour, another man entered and introduced himself as a Director of the Museum, Genadiy Bodnarchuk. He explained the entire complex and museum were found by his father, L.I. Bodnarchuk (1938-2015) and the museum itself is now named the L.I. Bodnarchuk Beekeeping Museum. We had a good laugh when he told us he is allergic to bees (a trait we share in common). Our friend who wanted to start an apiary had some questions and Gendaiy gladly spoke to them about the two different types of Apis mellifera used for beekeeping in Ukraine. There is what he called the “Steppe Bees” which are more adapted to warmer climates and live in the south of the country. Unfortunately, this is where most of the active war zone is and many beekeepers have lost their apiaries through death, destruction and theft by the invading army. The other type of honey bee used he called “Carpathian Bees” which he got very excited about. Apparently, these are very disease/pest resistant, gentle and he became animated as he explained that they forage in fairly cold temperatures compared to many others.

Genadiy is a very kind man who exudes a love for what he does but he couldn’t avoid being downcast as he explained that due to the war, almost all their funding has dried up. He barely scratched enough money together to fix a roof that collapsed during the Winter, nearly destroying some of the museum’s displays and archives. Officially, they could not generate revenue from visitors because there is no bomb shelter on the grounds so they cannot legally be open to the public. Genadiy still maintained a twinkle in his eye and a glimmer of hope like we all do who have endured this war so far. All of us chatted for nearly an hour as he showed us some experimental hives that they were also seeking funding for. Genadiy smiled as he told us that the Apimondia Congress had said that their museum “Featured a collection that no other museum in the world comes close to.” (https://www.apimondia2013.com.ua/technical-tours).

Photo 5 (Art by Alexandr Chekmenev)

Those events are long gone now and maybe they have all been forgotten. The free hosting of the museum’s website is long since expired. Grass and shrubs are overgrown in many areas of the grounds. No visitors can come. Many beekeepers throughout Ukraine have been killed as soldiers as well as being hit by Russian missiles and artillery. A picture of a Langstorth hive painted in the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag, floating in water from the detonation of the Nova Kakhovka Dam and its resulting floodwaters as the honey bees so desperately clung as a swarm on the outside still haunts me. The story from a Ukrainian Telegram Channel (https://t.me/pravdaGerashchenko_en/27050) of a sixty-eight year old beekeeper named Serhiy (Photo 5 by Alexandr Chekmenev) who managed to grab some honeycombs before running into an underground shelter with nine children and nine adults who made candles from the beeswax to provide light for the scared children. Seven of the adults were executed by the Russians and ten others died due to the conditions in the cellar. Serhiy survived but only two out of his forty-two hives survived. The longing and pain of the photo of a beekeeper who lost so much still circulates among all the other horrors of this war.

Natasha (now a U.S. citizen) always speaks fondly of her years in the U.S. and how she loves the kindness and generosity of Americans. We drove away and decided that despite being busy, dealing with our own war issues, that maybe we should start a Facebook page for the Petro Prokopovych National Beekeeping Museum. Here is this treasure of Ukraine and of international beekeeping history that may be lost or fall into serious disrepair because of the actions of a murderous enemy that is trying to destroy Ukrainian history, culture and people. According to some sources, Ukraine is the top honey producer in Europe and in the top five countries worldwide. Yet, there is no mechanism beyond this small operation to conduct experiments, catalogue beekeepers, pests, diseases and promote beekeeping in Ukraine. Here, in the place where the first commercial beehive was invented, there is little hope among the staff that anyone will help. The value alone for beekeepers in North America related to the Carpathian and Steppes variant bees is enough for someone to come to the rescue. Then, I thought, well, maybe if people there actually knew the story, those values that Natasha cherishes so much would immediately come into play.

Author Bio

John Gordon Sennett is a U.S. citizen living in Ukraine since November 2020 with his wife Natasha (Prokopvych). Natasha’s family in Ukraine has a long history of beekeeping. She bought John a hive for his 50th birthday and he was hooked. John was an urban hobbyist beekeeper in Lakeland, Florida for four years where he was an active member of the Ridge Beekeeper’s Association in Polk County and kept three modified Langstroth Long Hives with feral bees.

Paypal to donate to the National Beekeeping Museum: bee_kievmuseum@ukr.net