By Paola Tamma | EURACTIV.com

France loves honey. But is it real?

Cheap imports of counterfeit honey are endangering beekeeping around the world, and the consequences for world food production are severe.

Foreign sugars were found 1.4 times in every 10 honey samples tested by the European Joint Research Centre, according to research published in December 2016.

The research was undertaken in response to a report by the European Parliament on the most faked foods, in which honey was ranked 6th.

Researchers tested a total of 2,264 honey samples from all EU member states (plus Norway and Switzerland) which were collected at all stages of the supply chain.

Around 20% of honey either declared as blends of EU honey or unblended honey bearing a geographical reference related to a member state were found to be suspicious of containing added sugar. The rate of suspicious honey was around 10% for blends of EU and non-EU honey, blends of non-EU honey and honey of unknown origin.

Faking honey

Honey fraud can take different forms. For instance, by selling cheaper multifloral honey as single source honey at a higher selling point; by adding sugar syrups to increase the volume, or by harvesting it ahead of time and then drying it artificially in large “honey factories”, to cut time and costs. In all cases, the final product is far from what consumers think they’re buying, as well as from the EU’s legal definition of honey.

The EU defines honey as “the natural sweet substance produced by Apis mellifera bees from the nectar of plants […], which the bees collect, transform by combining with specific substances of their own, deposit, dehydrate, store and leave in honeycombs to ripen and mature”.

Member states must conduct lab tests on the honey they produce and import, by checking parameters like origins and levels of pollen, moisture, and the presence of added sugars. But testing methods vary and honey fraudsters have a steep learning curve.

“There is no single method for authenticity testing for honey – because there are so many ways of adulteration,” says Dr Stephan Schwarzinger, a professor of structural biology at the University of Bayreuth.

“It’s like doping analysis in sports. The people who are testing for doping never know if there is a new drug on the market. When you consider the variety of syrups available, there is no single technology that would cover them all. You need to have a look at many chemical and physical parameters.”

To counter the difficulty of spotting fake honey, Dr Schwarzinger had the idea of applying nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to honey testing. Magnetic waves deliver a “fingerprint” of the honey, which is compared with a reference database of 10,000 worldwide samples. Based on matching profiles, it is possible to know whether the label is lying.

NMR is much more efficient and effective as a method for honey testing, yet it is not widely adopted because of the slow uptake of new technologies in the food sector, the need for a scientific consensus, and resistance from the industry.

“Imagine you bought large quantities of honey, and then this new method tells you that all your stock is adulterated. This surely is a source of resistance to adopting new, safer methods,” said Schwarzinger.

Chinese honey factories

Europeans love honey, and eat on average 0.7kg per year, with Greece and Austria leading the pack at 1.7kg per capita.

But Europe eats more honey than it produces – and turns to China for 50% of its honey imports. The largest importers are the UK, Belgium and Spain.

China has become the world’s largest producer of honey, with 473,600 tonnes produced in 2014 (compared to the EU’s 161,031).

Between 2000 and 2014, according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization, its production has increased by 88% driven by a rise in exports. Sales of honey earned China $276.6 million (€231 million) in 2016.

But the number of beehives over the same period only increased by 21%. China’s bee population is declining, like everywhere else in the world, due to pesticide poisoning, pollution, and a loss of bee habitat due to urbanization.

All of these factors affect the bees’ immune system, and colonies decline their numbers. Pictures of Chinese farmers pollinating their fruit trees by hand have become a symbol of high pollution.

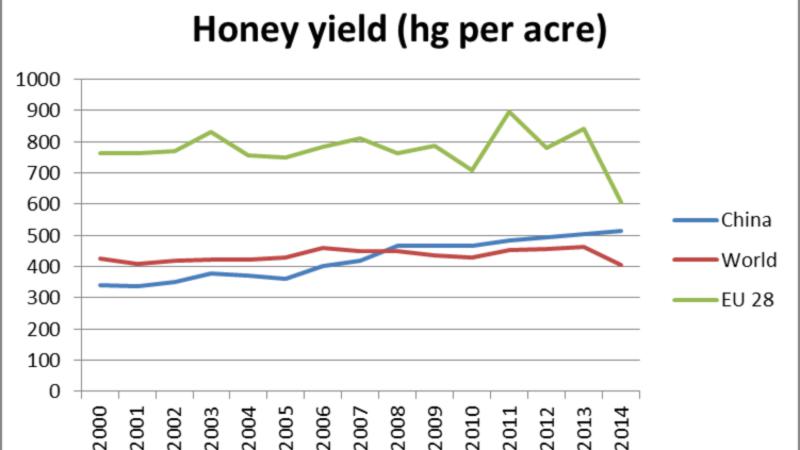

Productivity per beehive around the world is dropping – so how can the Chinese bees deliver such a high yield?

FAO data

The answer is China’s production method. Unripe honey is harvested when it is still a watery soup with high water contents. It is then artificially dried, resin residues are eliminated by filtering, pollen may be removed or added to mask country of origin, and syrups are added to meet the different market prices.

“Unripe honey production implies faster and higher levels of production of a product that does not meet the definition of honey (fraud),” said Norberto Garcia, president of the International Organisation of Honey Exporters (IHEO).

The Argentinian professor has studied the phenomenon of honey fraud closely and claims it costs about $600 million a year in income losses to honest beekeepers worldwide.

“There is a roof for honey production and we have reached that roof in many cases, but demand doesn’t stop increasing.”

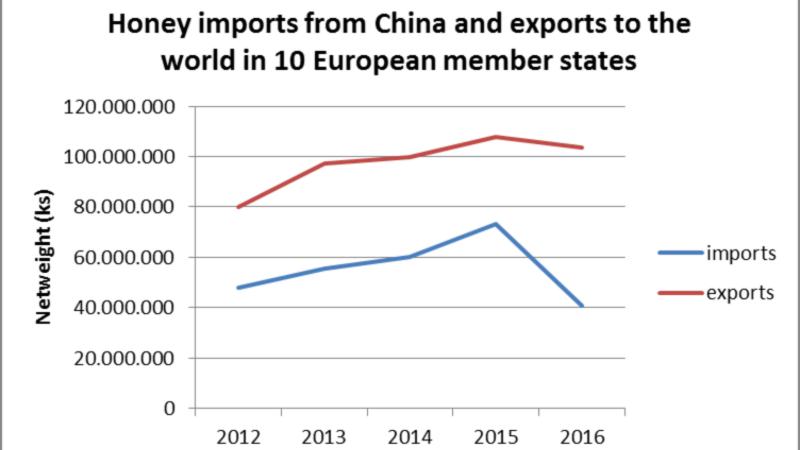

Cheap Chinese honey could have constituted an incentive for several European countries to import cheap honey from China and then re-export it as locally produced.

A number of European countries have seen their honey exports increase dramatically in parallel with their imports from China, as shown in the graph below for a selection of European states (Spain, Slovakia, Portugal, Poland, Netherlands, Lithuania, Italy, Ireland, Germany and Belgium).

“There is a great market inside the EU which should be checked more deeply,” said Garcia.

Increased consumer awareness also pushed importers away from Chinese honey, and European supermarkets are increasingly adopting NMR testing to avoid food fraud.

He says that because of the huge flow of fake honey which has been driving down the price of bulk honey globally, in 2017 Chinese exporters cannot compete with pure honey at current prices.

The Chinese sanitary authority (AQSIS) is now severely controlling the quality of export honey, especially to the EU, in order to limit losses.

This has caused Chinese honey exports to Europe to dip by 3% in 2016, after peaking in 2015.

But relying on the market to regulate itself only works until economic incentives are aligned with consumers’ interests, which is usually the exception and not the normThe European Commission will not block member states’ attempts to sue China over its use of counterfeit trademarks and has insisted a future bilateral deal with the Asian superpower will bring “significant benefits” for Europe’s quality food producers.

Honey law

Chinese honey flooding Europe is not a new thing. Between 2002 and 2004, Chinese honey was banned in the European Union because of a lack of origin labelling and a risk that it contained lead.

However, the ban was lifted due to increased demand, which Europe could not satisfy elsewhere, and European honey importers have jumped at the opportunity.

Honey is regulated in the EU by the Honey Directive, but the requirements for declaring the origin of honey are extremely low. Labels can read “blend of EU honeys” (e.g. a mix of honey from more than one member state), “blend of non-EU honeys” (a mix of honey from more than one country outside the EU), “blend of EU and non-EU honeys” (e.g. a mix of EU and non-EU honey).

“Most of the honey that you find is labelled blend of EU and non-EU honey – there are no standards. The information on the label tells consumers nothing, except that this honey is not from Mars,” says Walter Haefeker, head of the European Beekeepers’ Association.

There have been initiatives in the Parliament to amend this directive, in order to include the countries of origin on the label and a blend ratio.

Romanian Partidul Social Democrat MEP Daciana Sârbu (S&D) said: “The demand for honey is high and European production is limited. Imports from third countries are needed, but some honey imports are suspected to be produced not from pollen, but other, non-natural sources. The European Commission and the member states need to ensure that the honey placed on the market is not counterfeit. To achieve this, more controls at the packing companies are required.”

European and US government and trade officials say they have been lobbying hard against a draft Chinese regulation on food imports, worried it would hamper billions of dollars of shipments to the world’s No.2 economy of everything from pasta to coffee and biscuits.

But so far the Commission has been deaf to beekeepers’ requests.

“Responsible in the end is the Commission – if the commission would finally allow for [specifying] the origin of honey, it would enable consumers to make better choices, and this would put pressure on the industry to clean up its act,” lamented Haefeker.

“But for them, free trade is almost a religion and consumer protection is something they have to be dragged towards kicking and screaming,” he added.

Environmental impacts

The issue is not just for beekeepers:. Pollinators like bees and other insects are responsible for 35% of the world’s food crops according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation. And because of decline in other species, honey bees are increasingly bearing the brunt.

“The drop in (the) honey bee population is not as severe [as other insects], as beekeepers always try to make up for the losses. This results in honey bees being more and more important for pollination because the other pollinators are gone. You have an ageing population because it is economically unattractive. If the economics of beekeeping are gone, there is no incentive to reconstitute the colonies after the losses,” warned Haefeker.